Thomas D. Rossing, Rossing@physics.niu.edu

Physics Department

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115

Popular version of paper 4pAA1

Presented Thursday afternoon, November 4, 1999

138th ASA Meeting, Columbus, Ohio

Many ancient Chinese bells, some more than 3000 years old, remain from the time of the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Most of these bells, being oval or almond-shaped, sound two distinctly different musical tones, depending upon where they are struck. Studies of these bells have provided us with much knowledge about the musical culture of Bronze age China.

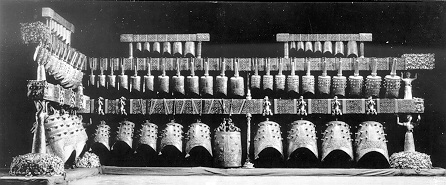

Most musical bells were manufactured in scaled sets of chimes. Chimes of bells were frequently buried in the tombs of royalty and noblemen, and that is how large numbers of ancient bells have been well preserved through the ages. The most remarkable set of bells discovered to date is the 65-bell set discovered in the tomb of Zeng Hou Yi (Marquis Yi of Zeng) in 1977 (see photo). The richly-inscribed bells survived in excellent condition since about 433 BC due to the tomb filling with water. Many other tombs have yielded sets of bells, but only a few of them have yet been studied acoustically.

We have recorded the sounds and made acoustical measurements on several original bells in the Shanghai Museum and in the Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Vibrational modes in original bells, obtained by experimental modal testing in these two museums, compare very well with holographic interferograms of replica bells. Although these acoustical studies have revealed a great deal about ancient Chinese music and casting practices, several questions still remain unanswered. For example, we dont know how the ancient bell designers determined the musical interval between the two notes.

The inscriptions on the Zeng Hou Yi bells indicate two intended intervals between the A-tone and the B-tone, corresponding to a major third and a minor third in Western notation. The measured intervals for the 65 bells show some clustering around 300 cents (minor third) and 400 cents (major third), but they cover a considerably wider range (about 210 cents to 490 cents, where 1200 cents represents a full octave).

Our studies show that the musical intervals between the two tones do not correlate well with the width-to-depth ratios (eccentricity) of the bells, the height of the arch at the rim, or the thickness contours of the bells, the physical dimensions that might be expected to control the intervals. How, then, did the ancient bell casters control or predict the intervals? Having no electronic instruments or reliable tuning standards, the ancient founders could tune only by ear. It is not at all unlikely that they cast many bells, selected the ones whose sounds they liked and melted down the others to the re-cast. Tuning of the A-tone may have been a more important criterion for acceptance than the A-tone/B-tone interval.

However well the ancient Chinese bell founders were able to predict or control the tone separation in the two-tone bells they cast, their casting skills were remarkable for their time. After thousands of years, many of the bells still remain musical instruments of high quality!