Cynthia G. Clopper - cclopper@indiana.edu

David B. Pisoni

Speech Research Laboratory

Psychology Department

Indiana University

Bloomington, IN 47405

(812) 855 4893

Popular version of paper 1aSC10

Presented Monday morning, June 4, 2001

141st ASA Meeting, Chicago, IL

Human speech is highly variable, despite the apparent ease with which we can understand those around us. In addition to providing a means of communication of ideas through words, speech also provides us with detailed information about the speaker, such as his or her gender, emotional state, age, and dialect. Variation due to these so-called "indexical" properties of the speaker has only begun to be studied systematically in the last few years. Understanding how variation is used in human speech perception is of fundamental importance to speech recognition, natural-sounding speech synthesis, and cognitive models of speech perception. The present investigation was designed to learn about how much people know about dialect variation in their native language. We wanted to know if naive listeners can identify where an unknown speaker is from with any degree of accuracy. Results from this study provide insight into what information about a talker's dialect is processed and stored in memory during normal speech perception.

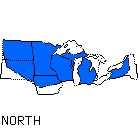

A group of eighteen Indiana University undergraduates was asked to listen to sentences spoken by sixty-six white, male talkers in their twenties. Eleven speakers came from each of six dialect regions in the United States: New England, North, North Midland, South Midland, South, and West. After hearing each sentence, the listeners were asked to select the geographical region that they thought each talker was from. The regions used for this study are shown in Figure 1.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

To hear a sample sentence from any of the regions, just click on the map corresponding to that region. The sentences were taken from the TIMIT Acoustic-Phonetic Continuous Speech Corpus, which is available from the Linguistics Data Consortium.

The two sentences used in this study were:

(1) She had your

dark suit in greasy wash water all year.

(2) Don't ask me to

carry an oily rag like that.

Overall performance on the task by the undergraduates was quite poor. Across the two different sentence conditions, accuracy was only 30 percent correct. However, analyses of the confusion matrices for the six regions revealed that the perceptual errors made by the listeners were quite systematic. Specifically, our listeners were able to reliably identify the talkers using broader perceptual categories than those used in this study. The broader categories and the regions they include are shown in Table 1. When performance was measured using these categories, accuracy for the two sentences improved to 60 percent correct. It appears that listeners are sensitive to certain phonetic and phonological properties of speech that provide useful information about where talkers are from.

| Category | Regions |

| North | New England, North |

| South | South, South Midland |

| West | North Midland, West |

Acoustic analyses were also carried out on the speech samples themselves to identify and measure the dialect differences for the talkers used in this study. Results of the analyses revealed that the dialects did differ from one another on several acoustic-phonetic measures. For example, r-lessness, as in "dak" for "dark," was a characteristic feature of the New England talkers. Click here to listen to a New England talker. On the other hand, saying "greazy" for "greasy" was a characteristic feature of the Southern talkers. Click here to listen to a Southern talker.

Correlations were then computed between the results of the categorization task and the acoustic analysis measures. The pattern of results suggested that listeners were in many cases relying on the characteristic features of the dialects when selecting where the talkers were from, again providing evidence that listeners are sensitive to dialect variation in speech. When we listen to speech, we not only pay attention to the words and the meanings those words convey, but we can also perceive, encode, and use indexical information in the speech signal to learn more about specific properties of the talker.