Dr C. Thomas Ault - ctault.@iup.edu

Umashankar Manthravadi - umashanks@yahoo.com

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Dept. of Theatre and Dance, Waller Hall

Indiana, PA 15705

Popular version of paper 4aAAb3

Presented Thursday morning, December 5, 2002

First Pan-American/Iberian Meeting on Acoustics, Cancun, Mexico

A 3rd Century BC theatre in India?

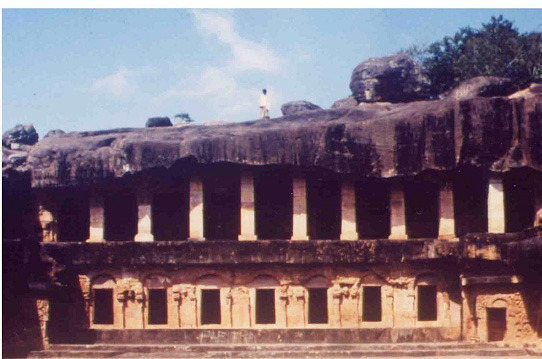

Rani Gumpha is the current local name given to the largest structure in a group of

excavated caves called Khandagiri, very close to Orissas state capital, Bhubaneswar. The structure dates to about 2 or 3 century BC, the period just after Ashoka.

In Indian archaeological terms, it is a very early site, and represents an

important transitional period in the countrys history. A long period of Greek

influence on the western side of India had begun to ebb, after Alexanders conquest,

and in the rise and decline of the Mauryas, had seen its first nation-wide empire.

It is an interesting site because it has no apparent religious function.

It is a very richly carved, elaborate, two-story structure, with evidence of

a considerable amount of wood work, which decayed away long ago.

In particular, there seems to have been a large wooden deck or platform extending

in front of the first floor. And the flat space in front of the structure

can accommodate a large audience.

Could this have been a theatre? Or at least, some kind of a performance space?

The suggestion has been put forward before, notably by art historian Percy Brown

and Dhiren Dash, a theatre activist from the region. But the general explanation

(offered by the Archaeological Survey India and others) has been that these

were just another set of caves set apart for meditation.

The elaborate carving in a series of friezes suggests a narrative of some

sorts, but no one has yet tried to link the images to any of the known epics

or ancient stories. There are images of dancers, performing in front of a seated

personage who could be a king.

Treatment of the space on which the dancers stand (this decoration is repeated

all along the frieze) suggests a kind of wooden platform that may have extended

in front. It appears to be dense and heavy, built up from many thick hewn logs.

The

structure is also very complex, with many small spaces connected with narrow

openings, which seem to have no real function, as well as curved floors and

rear walls.

Most remarkable of all is the acoustics of this space. It does not have the

kind of unusual acoustics frequently associated with archaeological sites

no odd echos, no whispering spaces. But if you stand and speak anywhere in the

performance area, you can be heard all along the audience space. A very much

louder sound than you would expect, very clear and detailed, with just enough

hint of reverberation to provide body to the sound. Certainly not the kind of

sound you would expect in an outdoor space. Remarkably, this effect disappears

just a foot or two away from the performance space (stage).

We had taken our first acoustic measurements of this space five or six years

ago, along with very detailed physical measurements of the site. Our early measurements

were somewhat crude, but these have been repeated in May of this year, and we

will be presenting our results at these sessions. Primarily, the measurements

go to confirm the aural quality of the space, putting numbers on the extraordinary

quality of the sound that anyone can hear.

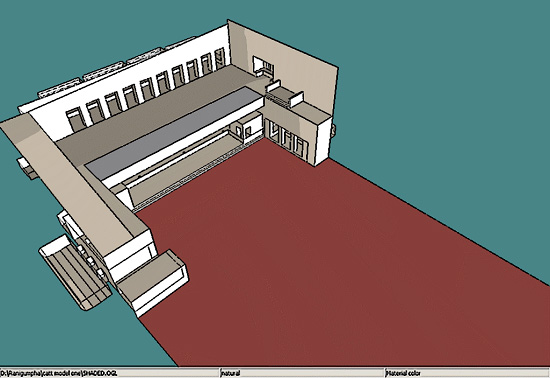

We

have simultaneously been building an acoustic model of the structure using

CATT acoustic software, and comparing the results generated by the model with

those obtained at the site. (The software has been developed to assist architects

in the construction of auditoria, by simulating their sound on a computer).

There

are several reasons for building this model. First, one can separate the

complex of interactions in the structure, and try to define which parts of the

building provide which elements of the sound. A second, more fascinating proposal

is the modification of the structure. Ranigumpha was carved out of rock. By

simulating this process in the model, carving the structure again, step by

step, we should be able evaluate the acoustic properties of the structure in

the intermediate stages, all the way to completion.

We think the builders of Ranigumpha proceeded the way a maker of musical instruments

does. The shape of the structure was predetermined: but the fine details were

determined by the sound they heard from the structure. The builders stopped

excavating further when the sound came out right. By building this structure

again, and listening to its sound, one might learn something of the aural acuity

of its builders.

We are not proposing that the builders of Ranigumpha (or other ancient sites

elsewhere in the world) possessed better hearing than us, or that they had early

and better version of acoustics. What they did have to their advantage was

an acoustic environment that was just very much quieter. No machinery noise,

no traffic, not even too many humans!

Reverberation

tails that now disappear into the general background noise, small changes in

coloration, would just have been very much more obvious then.

In

the long run, we hope to address some major puzzles in Indias cultural history.

Beginning from the 5th century BCE, there are numerous references in Indian

literature to theatre, to actors, and to performances. Paninis fifth century

BCE grammer uses the speech of actors to illustrate grammatical structures.

Kamasutra (a much later work) sets out in detail the responsibilities of a citizen

(nagarika) towards actors and their maintenance. Bharata's Natyasastra, compiled

between 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE, is the world's oldest manual on theatre.

It is also very comprehensive, beginning with the construction of theatres and

going on to forms of theatre, dance, music,poetry and figures of speech.

But

where are the theatres? In all the countless monuments excavated and preserved

in India, only two have been tentatively identified as "theatres"

and these definitions have not been universally accepted. We have been measuring

and modeling one of the two sites, and we plan to extend this to the other

possible theatre sites at Sitabenga in Ramgarh hills.

Our aim is to measure and model the acoustic properties of as many early sites

as possible (by early we mean the period between 3rd Century BCE to 3rd Century

CE). We do not wish to suggest that acoustics will completely answer one of

the puzzles of Indian Archaeology. But we hope it will provide clues.