Popular version of paper 4pSC8 Taken together, these findings confirm that babies are highly attentive to

the acoustical environment that surrounds them. With respect to music, researchers

have not explored infant perception of music that is considered complicated

by musical standards. This bias falls in line with the advice of music educators

who often recommend simple music for the infant ear. Our finding that infants

can remember a piece of complex music over a 2-week delay appears to challenge

this implicit assumption that infants are ill-equipped to handle complex music.

To investigate whether babies can remember complex music, we exposed a

group of 8-month-old infants to one of two piano pieces, Forlane or Prelude,

from the composition "Le Tombeau de Couperin" by Maurice Ravel (1875-1937).

Musicians agree that this work is complicated due to its intricate harmonies,

complex rhythmic motives and textures (see excerpts below). The parents of each

child were given a CD recording of either the Forlane or Prelude movement and

were asked to play the assigned piece three times daily for the baby for ten

consecutive days. Parents also completed a diary to document listening date,

time and infant mood. Diaries and CDs were collected at the end of the prescribed

listening period. Babies were brought to the university lab for testing two

weeks following the CD collection date.

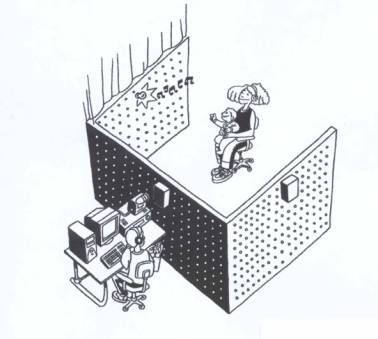

In

the lab, we tested each baby to see if they had a listening preference for one

of the two piano pieces using the Headturn Preference Procedure3 (see illustration

below).

The Headturn

Preference Procedure Our results showed that these infants displayed a preference for the piano

piece they heard. Babies exposed to the Forlane preferred to listen to it over

the Prelude and likewise, babies exposed to the Prelude piece preferred it over

the Forlane. We also tested a second group of babies who had never heard either

piece of music. These babies showed no preferences for either piece of music.

Taken together, these results show that babies had formed an impression of the

piano piece and were able to retain this impression over a 2-week delay.

To better understand whether complicated music is harder for babies to remember

than simple music, we compared our results with those found in a previous study

that used the same design and infants of the same age to see if infants could

remember a simple Mozart piece. This comparison shows that the preference effect

(the difference in listening time to the familiar versus the unfamiliar piece)

is stronger for more simple music. Thus, simple music may still be easier for

babies to encode than complicated music. Yet, babies were able to learn with

both simple and complex music. We don't know what information babies retained

from their exposure to either simple or complex music; was it the melody, or

some more global acoustic features of the music? This will require further systematic

investigation.

In sum, our study provides further proof that babies are keen listeners, able

to pick up and store information that is repeatedly presented in the acoustical

environment that surrounds them. Evidence that infants can remember complex

music is important for at least two reasons. Firstly, it helps us understand

whether babies have limitations to process music; if there is in fact music

that is appropriate for babies. Secondly, it is helpful for the elaboration

of curriculum for early childhood education. There are many related questions

to answer to fully address these general issues. What are the long-term effects

of such learning? Do children remember the music they heard when they were babies?

To what extent do musical experiences in infancy dictate people's later musical

taste? While we attempt to answer these questions, keep in mind that your baby

is also listening to that piano CD that you love so much. And learning. And

remembering.

Main

references:

1Jusczyk, P.W. & Hohne, E. A. (1997). Infants' memory for spoken

words. Science, 277, 1984-1986. 3 Kemler-Nelson, D.G., Jusczyk, P.W., Mandel, D.R., Myers, J., Turk,

A., & Gerken, L. (1995). The head-turn preference procedure for testing

auditory perception. Infant Behavior and Development, 18, 111-116.

This paper will presented at the 143rd Meeting of the Acoustical

Society of America on Thursday, June 6th at 1PM during session

4pSC - Speech Communication and Psychological and Physiological Acoustics:

Future of Infant Speech Perception Research: Session in Memory of Peter Jusczyk.

For

further information, please contact : beatriz.ilari@mail.mcgill.ca

Beatriz Ilari1, Linda Polka2 & Eugenia Costa-Giomi1

-beatriz.ilari@mail.mcgill.ca

McGill University, Montreal,

Canada

Faculty of Music1, School of Communication Sciences and Disorders2

Presented Thursday afternoon, June 6, 2002

143rd ASA Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA

Babies are great listeners. Hours from birth, a newborn can tell his mother's

voice from that of another woman. By about 4 months of age, a baby smiles and

shows recognition of his own name. Babies between 8 and 9 months of age can

remember words from a story1 or a simple piece of music2

that they heard previously, even after a two-week delay.

2 Saffran, J.R., Loman, M.M., Robertson, R.R.W. (2000). Infant

memory for musical experiences. Cognition,

77, B15-B23.