Amee P. Shah - amee.shah@mail.mcgill.ca

Research Laboratory in Speech Acoustics and Perception

Department of Speech and Hearing Cleveland State University

2121 Euclid Avenue, MC 431-B

Cleveland, OH 44115 (216) 687-6988

Popular version of Paper 4aSC1

Presented Thursday morning, November 18, 2004

148th ASA Meeting, San Diego, CA

Introduction

Please listen to this speech sample:

![]()

Does this sound like it is spoken by a nonnative speaker of English, a "foreign-accented"

speaker? My guess is, you, the listener, are not only able to correctly decide

that it is indeed a sample of foreign-accented speech--but many of you may even

be able to try and identify the native language of the speaker, i.e.,

Spanish in this case. It appears (as also confirmed by numerous research studies)

that native speakers of a language are not only able to reliably detect, but

also differentiate between different accents. The interesting question is: How

are we able to (so reliably) tell when speech is "accented," or different

from the native standard form? Are accents in the "tongue of the speaker"

or the "ear of the listener", or some combination thereof?

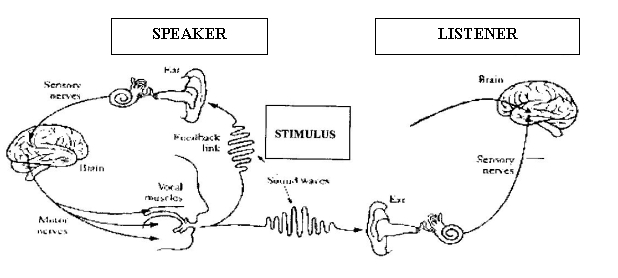

An examination of studies to date, in conjunction with findings from some of

my own research, suggests that there may be three sets of factors, i.e.,

a three-dimensional interaction, that apparently influence the production and

perception of foreign-accented speech. These three dimensions are akin to the

communication components seen in the "Speech Chain Model," i.e.,

variables related to the speaker, the speech per se, and the listener, all of

which form the chain from production to perception of speech, and as will be

shown in this paper, interact in the perception of accentedness.

Speaker-related Variables

First, extensive research findings substantiate the influence of speaker-related

variables in the presence of a foreign accent. Among these, differences in the

ages at which the nonnative speakers learn the second language are found to

predict whether the speaker will show the presence of a foreign accent in their

speech. The younger one learns a second language, the more native-like one sounds

in that language. Additionally, beyond a certain age range (the "critical"

or the "sensitive" period), usually by adolescence, learning a second

language will invariably leave the speaker with a trace of "foreign-ness"

in their speech, though they may have managed to master other aspects of language,

such as vocabulary and grammar, with native-like proficiency.

Another factor, while not as definitive as age of acquisition but also quite

significant in predicting the presence and the degree of foreign-accentedness,

is the length of period the nonnative speaker has spent in the region/country

of the second language. For example, the longer a Russian-accented speaker spends

in the U.S., the more native-like he/she will sound in English. However, it

has been shown that a stay beyond a 5-7 years' period of residence does not

necessarily predict further progress towards native-like patterns of speech

since learning may have "stabilized" at that point.

Of course, the length of residence in the nonnative country is often intertwined

with other psycho-social variables that determine whether the nonnative speakers

will gain ultimate native-like pronunciation. These are, to name a few, motivation-level

of the second-language learners; relatively greater amount of interaction with

native speakers of the language and correspondingly, relatively lesser amount

of interaction with other nonnative/ foreign-accented speakers; the gender of

the speakers; and other special abilities to perceive and produce the nonnative

sounds, including imitating and mimicking sounds, discriminating pitches and

so on. Thus, we can see that accented speech is not an exclusive listener-dependent

phenomenon, rather it is certainly also influenced by the differences in the

"tongues of the speakers."

Speech-related Variables

Turning to the second dimension, the speech-related variables, predicting

the presence of "accentedness" has been studied rather extensively

in the field. Findings show that the interlanguage differences in the phonetic

patterns of the speech of the nonnative speakers influence listeners' perception

of accentedness of nonnative speech.

Findings show that the speech of the nonnative speakers learning the second

language has systematic "interlanguage" features. That is, certain

sound properties borrowed from one's own language, and certain others that are

different from one's own language and more and more like those of the native

speakers of the second language. Interestingly, nonnative learners tend to be

consistently similar within the same language group, and markedly distinct from

those of a different language group. For example, Spanish-accented speakers

have consistently similar phonetic patterns as a group, and those are distinctly

different from German-accented speakers. It is, presumably, this systematic

difference that helps listeners characterize the differences across different

accents and influence their perception of accentedness.

Listener-related Variables

While we now know that accentedness has a physical basis, and is not simply

a perceptual illusion or a psychological construct shaped "in the ear (or

mind) of the listener," differences across listeners do tend to

influence the perception of accentedness, which is the third dimension that

completes the three-dimensional triad of perceived accentedness. Research indicates

that differences across listeners, in that whether they are native or nonnative

speakers themselves of the language in question and whether they share the language

group with the speakers they are listening to, will greatly influence their

sensitivity in detecting and differentiating a foreign accent. Relatedly, if

the listeners are native listeners of the language in question, the fact that

they may have received prior listening experience with foreign-accented speakers,

in general, and the specific accent in particular, will likely influence their

perception of accentedness. Further, the amount of exposure to a specific foreign

accent will also likely reduce the listeners' perception of the degree of the

accentedness for that speaker. Over time, listeners tend to become better familiarized

with the idiosyncrasies of that speakers' accented speech, and may not only

be able to understand the speaker better, but also may think that the speakers'

speech has become "less accented"! Yet another variable that determines

listeners' acuity in perceiving accented speech is the listening condition in

which they hear the accented speech; the noisier the conditions, the greater

the difficulty listening to accented speech, and the stronger will the accent

be perceived to be. Finally, listeners' preferences and biases for certain language

and/or ethnic groups will tend to affect how they perceive the accented speech

that is spoken by those nonnative speaker groups. On the other hand, special

listening skills and phonetic training, if any, increase the sensitivity with

which listeners can discern the variations in accented speech.

Conclusion

This collective evidence from research in each of the three sets of variables,

speaker-related, speech-related and listener-related, has raised many questions

for the theoretical understanding formed within the scientific community. Controversies

have ranged over areas such as the importance of critical period in predicting

the ultimate attainment of second-language proficiency, the linguistic environment

that shapes the perception for a second language, children's perceptual shaping

in the second language over the developmental period, to name a few. Similarly,

extensive research in each of these areas has yielded findings that have served

as the bases to plan training approaches in ESL classrooms, or accent-modification

programs. That is, questions such as whether to target the speech sounds per

se or the prosody (rhythm) of speech in the training programs in order to make

the foreign-accented speaker perceived to be more intelligible to listeners.

Finally, the theoretical constructs and practical implications have served in

speech technological advances as well. Automatic speech recognition systems,

speech processing models, voice-activated devices incorporating speaker differences

due to foreign accents have become areas of active research and development.