|

ORGANIZING AND RECOGNIZING MUSICAL TENSION/RELEASE PATTERNS MAY BE

CULTURE DEPENDENT

Performing and listening to an improvisation

on the Middle Eastern mijwiz

Pantelis N. Vassilakis, Ph.D.

DePaul University School of Music

804 W. Belden Ave. Chicago, IL 60614-3250

http://www.acousticslab.com -

pantelis@acousticslab.com

Popular version of paper 3aMU5

Presented Wednesday morning, May 18, 2005

149th ASA Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada

|

|

|

|

Overview: Musical tension/release and auditory roughness contrasts

Our ability to attach meaningful

and emotional qualities to instrumental pieces of music relies, to a

large extent, on our recognition of potential musical tension/release patterns within a piece. Such patterns can be set up using a

variety of sonic and sonic-organization tools, whose significance

and potential to communicate meaning and emotion

appears to largely depend on previous small-scale (personal) and

large-scale (cultural) learning.

Within the Western musical tradition, studies have shown

that musical tension/release judgments are linked to contrasts in

terms of: i) tonal center (e.g. key), ii) sensory dissonance, iii) dynamics, iv)

pitch, v) rhythm, vi) orchestration, vii) performance techniques, etc.,

with sensory dissonance correlating with the presence of auditory

roughness. The term auditory roughness describes a rattling sound associated with certain types of signals

such as those of narrow harmonic intervals. The potency of the

suggested contrasts depends on familiarity with musical norms that

are, largely, culturally defined.

As the above list suggests, auditory roughness

contrasts within a piece constitute just one of the

sonic tools (cues) that help set-up (determine) musical

tension/release patterns. In addition, the strong link, within

Western tradition, between roughness and annoyance, and the

assumption that rough sounds should be avoided, limit the range of

roughness variations explored, further reducing the contribution of

auditory roughness contrasts to the organization and recognition of musical tension

and release.

As we will see, the situation may be quite different when it comes to

non-Western musical traditions.

|

|

|

|

A Matter of Audience: Auditory roughness contrasts in

non-Western musical traditions

Performance practices outside

the Western art musical tradition explore a much wider roughness

range, indicating that the sensation of roughness can be of much more

importance in the production of musical sound and the

communication of expressive intent. In many such cases, the

increased importance of auditory roughness as a sonic and

sonic-organization device is accompanied by a decrease in the

importance of other relevant devices.

For example, the Middle

Eastern mijwiz (two paired single-reed pipes) is constructed and performed in

ways that limit the possibilities for extensive exploration of

dynamic, pitch, tonal, and timbral (other than roughness) contrasts.

More specifically, the mijwiz:

a) requires performers to maintain high pressure air-flow in order

to sustain a steady tone, limiting its dynamic range;

b) is often performed using the circular

breathing technique, limiting the possibilities for interplay

between sound and silence;

c) has narrow

melodic range (~a fifth) and limited harmonic menu (no melodic line

crossing), resulting in limited possibilities for melodic/harmonic

contrasts;

d) has two reeds that are activated just by

air pressure (with no manipulation possible from the lips or tongue,

as would be the case for a clarinet-like instrument), limiting the

possibilities for timbral contrasts associated with vibrato or other forms

of spectral manipulation.

|

For its expressive power, the mijwiz, like

most double-pipes throughout history, relies mainly on the

exploration of narrow harmonic intervals. Such explorations

correspond to

manipulation and exploration of roughness degrees, making

musical pieces performed on the mijwiz good candidates for the

examination of the relationship between roughness profiles and

patterns of musical tension.

Click on the image to the right

to see a performance of the mijwiz piece used in the present study.

[Real

format - Click here to download a

free Real Player - IE 6.0 / Netscape 7.0 or later required] |

|

|

|

|

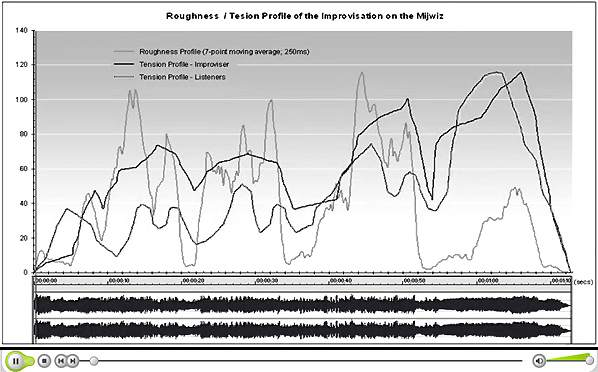

A Perceptual Study: Auditory

roughness profiles and tension/release patterns in an improvisation

on the Middle Eastern mijwiz

The present study examined a

recording of a stylized improvisation on the mijwiz, performed by

Prof. A. J. Racy, a Lebanese-born musician and scholar at the University of

California, Los Angeles, Department of Ethnomusicology (click on the

image above to see the

performance).

The roughness profile of the recorded piece was

estimated using a custom application that automates frequency

analysis and roughness calculation of complex signals, at

user-specified time intervals.

The application is

available online (http://www.acousticslab.com/roughness),

including detailed descriptions of the relevant analysis and calculation

methods. Briefly, the frequency analysis portion uses an improved STFT

algorithm based on the Reassigned Bandwidth-Enhanced Additive Model

by Dr. K. Fitz, while the roughness calculation portion is based on

a roughness estimation model introduced and tested in a previous

study by the author.

The roughness profile was compared to

tension/release patterns indicated by the improviser and expert

mijwiz player as well as by Western-trained musicians, in a

perceptual experiment designed using Prof. R. A. Kendall's Music

Experiment Development System (MEDS).

The results suggest that auditory roughness is a good predictor of

the tension/release pattern indicated by the improviser. The

patterns obtained by the subjects show a different trend. Auditory

roughness appears to be just one of the cues guiding musical tension

judgments, often overridden by tonal and temporal cues, as well as

by expectations of tension/resolution raised by such cues.

Click on

the image below to see a video clip of the results.

|

|

|

|

Discussion: Same musical piece

different musical understandings

|

|

The results may be interpreted

in terms of different listening strategies employed by the two

different types of listeners, strategies that are related to

musical expectations outlined by the

different underlying musical traditions.

From the improviser's point of

view, roughness contrasts created

through frequent moves between narrow and unison harmonic intervals

constitute musical expressive cues that are widely accepted and employed

within the Near Eastern musical tradition to communicate changes in musical tension. Composers

and performers incorporate

these contrasts when setting up tension/release patterns and

listeners look out for them, even if implicitly, when they

organize perceptually and attach meaning to musical pieces.

From the point of view of

listeners raised within the Western musical tradition, auditory

roughness contrasts play a limited role when it comes to identifying

musical tension/release patterns, while tonal and temporal contrasts

provide more significant musical cues and set up stronger

tension/resolution expectations. As a result, when Western

raised/trained listeners are confronted with a musical piece such as

the one used in the present study, they continue to employ their

familiar strategies to parse the incoming sound, reaching an

interpretation that differs from the composers /

performers expressive intent.

The observed differences between the tension/release patterns

obtained, correspond to differences in the way relevant (to each

listener type) musical

cues are laid out in time within the mijwiz piece. For

example, points in the piece corresponding to high (low) roughness

values but low (high) tonal or temporal 'load', coincide with high

(low) tension judgments by the improviser but low (high) tension

judgments by the Western-trained listeners. This supports the suggestion that musical

tension and release are

culture-specific concepts, guided by the equally culture-specific

musical cues used to organize and recognize them.

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgements

Study supported by the Department of

Instructional Technology Development and the School of Music, DePaul

University. Special thanks to Profs. R. A. Kendall and A. J. Racy,

Ethnomusicology Department, University of California, Los Angeles,

for their expertise.

|

|