Nocturnal Activity by Transient Killer Whales

at St. Paul Island, Alaska

Kelly Newman - k.newman@sfos.uaf.edu Popular version of paper 3aAB4 |

Transient killer whales Transient killer whales (click picture to hear their sounds) |

Over half of the world’s northern fur seals inhabit the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea off the coast of Alaska. Their luxurious pelts have been sought after for centuries and excessive harvesting has twice led to massive declines in the population since their breeding rookeries were first discovered in 1786 by Russian explorers seeking the fabled Fur Seal Islands. Conservation measures were enacted both times that saved the fur seals from extinction, and by the 1950s, the population had recovered to an estimated 2 million animals. However, misguided management in the 1960s led to yet another decline in abundance. Even when it was corrected, the population continued to fall for unknown reasons, and today the number of pups produced each years is less than 25 percent of the peak in 1950.

The trend in the population since the mid-1970s follows a large-scale pattern of population decline in the Bering Sea. Three other species of marine mammals—Steller sea lions, sea otters, and harbor seals also have suffered severe population collapses of 80 percent to 90 percent. Researchers disagree on the cause of these dramatic changes, with the blame attributed to food limitation, climate change, commercial fishing or the rise in predation by the chief natural nemesis of all of these species, killer whales.

Our project focuses on the predation hypothesis, which we are examining at the Pribilof Islands, a predation hot spot for killer whales, where they are common in summer and are known to feed on fur seals. But the Pribilof Islands are remote in the middle of an unpredictable sea, and difficult field conditions and poor visibility hamper efforts to observe killer whales and feeding episodes. This is perhaps why the bulk of the feeding observations of killer whales are from areas with calm waters such as southeast Alaska and Monterey Bay, Calif. While these reports offer valuable information on feeding behavior, they are based on small sample sizes and do not necessarily reflect what is going on in the rest of the ocean.

This presents a challenge: how can one accurately measure predation and behavior in areas where traditional search techniques simply will not work? One solution is to use alternative techniques to get a glimpse of behaviors that are not ordinarily “visible,” such as passive acoustic monitoring, or “eavesdropping,” which can be eight times as effective as using visual means only for detecting marine mammals. It works especially well for studying killer whales because of the strategies they use when hunting their prey. Seals and other marine mammals are particularly sensitive to movements and sound in the water, and will react to the sounds of marine-mammal eating, or “transient” killer whales (another type of killer whales feeds only on fish and their sounds are not alarming to other species). In response, transient killer whales are silent as they stalk their prey in order to escape detection. But after an attack is launched and a kill is made, they become highly vocal and are easy to detect acoustically.

Figure 1. We placed an autonomous recording unit (a “Pop Up”) off the coast of several fur seal rookeries on St. Paul Island during the northern fur seal pupping season. The names of each rookery are indicated, as well as the location of the Pop Up.

Therefore, we deployed a “Pop Up” Autonomous Recording Unit in the water offshore from St. Paul Island, one of the Pribilof Islands, from June 22 to July 12 last year at a predation hot spot near several northern fur seal rookeries (see Figure 1, above).

The sampling rate frequency range of our equipment was 10-16,000 Hz, which is sufficient to record transient killer whale calls and whistles. An important element of this work was that it expanded our observational window for killer whales to the complete 24 hour cycle, as darkness became irrelevant.

Our pilot study produced three important results: killer whales visit the island on a daily basis, they are more vocally active at night than during the day and they produce a large variety of calls. We detected whales on 19 of 20 days, with significantly more activity between midnight and 8 a.m. than during other hours. We were not surprised that killer whales are nocturnal because they, like most marine mammals, are adapted for limited visibility. However, we were surprised at how active they are at night (see Figure 2, below).

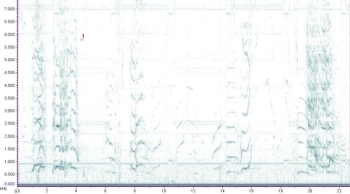

Figure 2. These vocalizations were recorded at 3:45 AM on July 8, 2006 off of St. Paul Island.

Click the picture to hear a sound recording.

Interestingly, nighttime is when fur seals typically depart the rookeries on their trips to forage. Since we know that killer whales are very vocal during and after a kill, our data can be used to assess potential predation rates (see Figure 3, below).

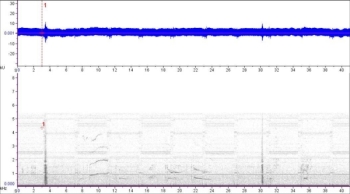

Figure 3. These loud impulse sounds, interspersed with calls, indicate physical contact between orcas and fur seals in the act of predation. These types of sounds frequently precede a series of vocalizations.

Click the picture to hear these sounds.

Passive acoustic recording coupled with visual efforts is a powerful way to locate whales. We had some correlated visual sightings and found our killer whale acoustic detection matched on most of the observations.

Our data have also revealed many different calls types, and those formerly categorized as variable or “aberrant” by previous investigators may provide meaningful information on the feeding behavior of transient killer whales. Furthermore, transient killer whales do sometimes vocalize when they are not feeding, and these calls should be compared to the more common call types.

Other researchers have focused on visual techniques to detect predation activity. In light of this, the great amount of nocturnal predation we documented raises new questions concerning the ecological role of killer whales, and suggests that attempts to quantify the impact of killer whale predation are meaningless with limited observational power. This summer we plan to continue to combine acoustic and visual observations, and acoustically map the Pribilof Islands for killer whale activity with a large-scale acoustic array. This will give us a better idea of which killer whales are visiting the rookeries, how often and how much they prey on fur seals.