Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

[ Lay Language Paper Index | Press Room ]

Val Schmidt- vschmidt@ccom.unh.edu

Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping 24 Colovos Road

Durham, NH 03820

Tom Weber

Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping 24 Colovos Road

Durham, NH 03820

Dave Wiley

Stellwagen Bank Marine Sanctuary, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association, Situate, MA 02066

Mark Johnson

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543

Erik Dawe

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543

Colin Ware

Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping 24 Colovos Road

Durham, NH 03820

Roland Arsenault

Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping 24 Colovos Road

Durham, NH 03820

Popular version of paper 3aAB7

Presented Thursday morning, November 29th, 2007

154th ASA Meeting, New Orleans, LA

Since 2004, scientists have been tagging and tracking humpback whales in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary to better understand their behavior. Stellwagen Bank is a shoal area East of Boston and North of Cape Cod, MA, where many species of baleen whale feed during the summer months.

Instrument tags with the ability to make underwater acoustic recordings (Digital Acoustic Recording Tags or DTAGS) are suction-cupped to each whale's back using a long pole from a rubber-hulled inflatable boat. The DTAGS, developed at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, also record whale pitch, roll, and heading, 3-D acceleration, depth and sound for up to 20 hours. Although the acoustic recordings give scientists the ability to listen in on whale conversations, one must know the whale's movements underwater in order to put the whale calls in proper context. For example, whales are known to make different calls when feeding or breeding.

Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

Knowing the whale movements underwater is exceedingly difficult, as one cannot simply peer into the ocean and watch from the surface. In the past, the track of the tagged whale has been predicted using visual fixes at the surface and dead reckoning while the whale is underwater. Dead reckoning is the process of calculating the whale's future position by knowing the whale's current position and its direction of travel. While whale tracks calculated in this way are helpful, they suffer from uncertainties that may preclude a full understanding of whale behaviors. A more reliable method is needed.

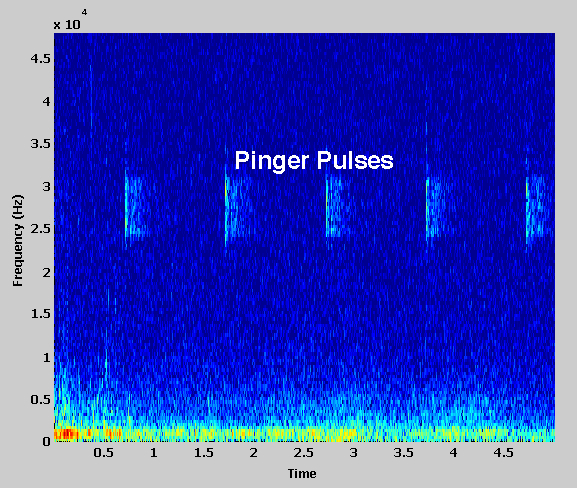

We, therefore, endeavored to design a system by which one can measure continuous whale positions while the tag is attached, so that a "true" whale track can be created, mostly free of drift and other uncertainties. To do this, we built three acoustic "pingers" which operate at 25-31kHz -- well above that of human (and humpback whale) hearing. Each pinger sends an encoded pulse, once per second, exactly on the second, using an inexpensive Global Positioning System receiver for triggering. Pulses from the pingers are recorded on the tag along with the whale vocalizations and other ocean background noise.

Each pinger sends one of six types of pulses, shown in each of the three rows above. A new pulse is sent every 10 seconds and all six are repeated each minute. Each pulse is comprised of seven tones, illustrated as orange dots in the spectrograms above. Similar to notes on a musical scale, the higher the dot, the higher the frequency of the tone. The order of the tones is permutated to create 18 unique pulses - six pulses for each of the three pingers.

The pingers are deployed from each of three small boats. The positions of the boats are recorded using GPS. By knowing the time that each pulse was sent, the time that each pulse is received on the whale's tag, and the speed of sound in seawater, we can calculate the range from the pinger to the whale. The three ranges from each of the three boats can then be used to triangulate a position for the whale. The process is much the same way a GPS receiver determines its position by measuring the travel time of electronic pulses from satellites.

To ensure that we could match the receipt of a given ping with the time it was sent and the corresponding position of the boat, we encoded a time signal into the acoustic pulses sent by the pinger. The encoding also allows us to distinguish one pinger from another.

Whale tag recorded acoustic data showing pinger pulses.

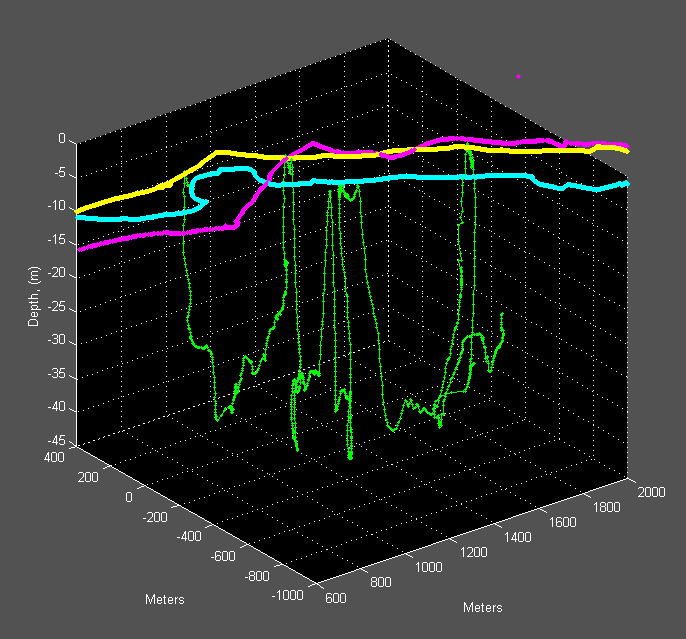

From our acoustically derived positions we have created a preliminary whale track for the humpback whale, 'Geometry'. [Scientists identify and name individual whales so they may be monitored from season to season.] A short segment of time during a DTAG deployment is shown above. In the illustration the tracks of the whale tracking boats are shown in yellow, magenta and cyan. The track of the Geometry is shown in green below. Several excursions into very deep water are clearly evident.

Acoustically measured whale track is shown in green with the track of the tracking team boats in yellow, cyan and magenta. (Vertical exaggeration = ~30 for clarity.)

All photographs in this presentation are property of the New England Whale Center and the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (unless otherwise noted) and used with their permission.