Challenges and Opportunities for Noise Mapping in the

United States

Kenneth Kaliski, P.E., INCE Bd. Cert.

Resource Systems Group, Inc.

55 Railroad Row

White River Junction, VT 05001

United States of America

Country code 1 plus 802-295-4999

kkaliski@rsginc.com

Introduction

Primarily through the impetus of European Union Directive 2002/49/EC, EU cities have

been at the forefront of noise mapping and the community planning that result from it.

Noise mapping efforts in the US have lagged behind those in Europe for three reasons.

First and foremost, thehe United States has no similar legislation at federal or state levels.

Second, the United States has less than half the population density of the EU. Third, and

an outgrowth of the first two, planners in the US are less generally aware of noise issues

than their European counterparts.

However, U.S. metropolitan areas have invested a great deal in transportation modeling. As a result, the data foundation for noise mapping—that is, road and rail geometry and traffic volumes—is in place in many metropolitan areas. In addition, digital terrain elevation data, aerial photography, and GIS data are generally available on a state or national basis at no charge over the Internet. Using these tools, several communities have begun the process of creating effective noise mapping and planning.

This paper gives examples of noise mapping in the United States and discusses challenges and opportunities for continued noise mapping.

Examples of Noise Mapping in the U.S.

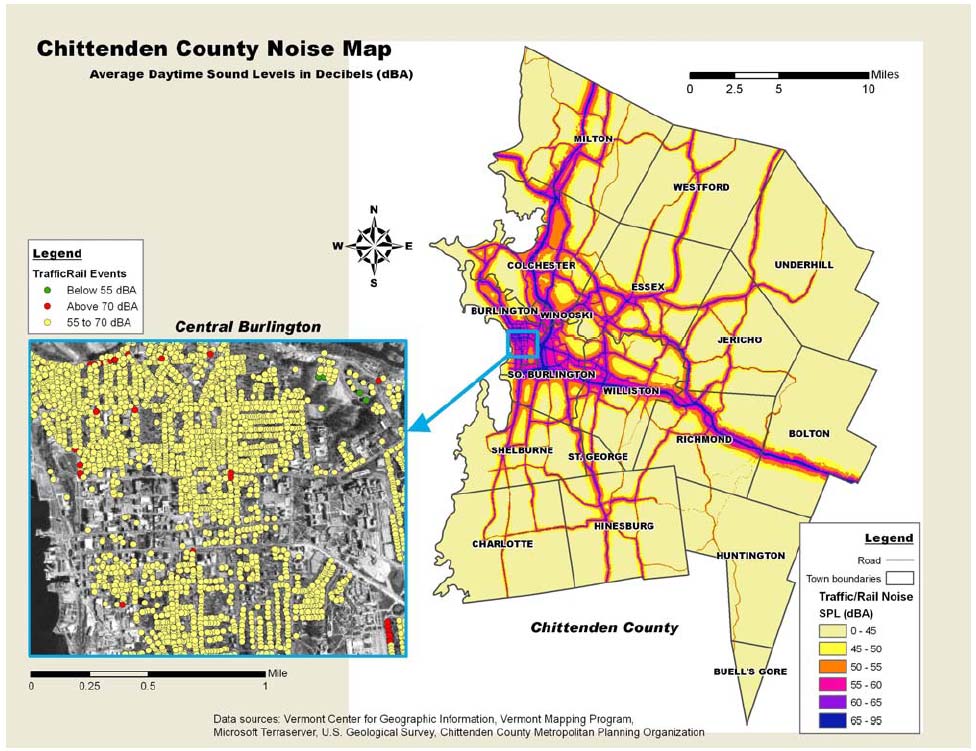

Chittenden County, Vermont

The first European-style noise map in the United States was probably one created for Chittenden County in Vermont. This noise map, produced in 2004, took into account all of the major roads in the county, railroads, the attenuation of high-density building areas, and terrain. The output showed a noise grid over the entire county and ranges of levels for each home.

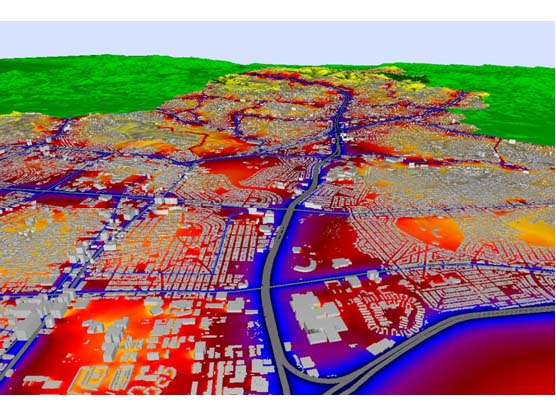

San Juan, Puerto Rico

The San Juan noise map, developed in April 2007, was one of the first large-scale noise map generated in the U.S. by a state Agency. It was develop by the Noise Control Area of the Environmental Quality Board of Puerto Rico, with the support of ACCON, to promote the use of the technology by municipalities to better study and manage environmental noise as part of Puerto Rico’s Noise Action Plan

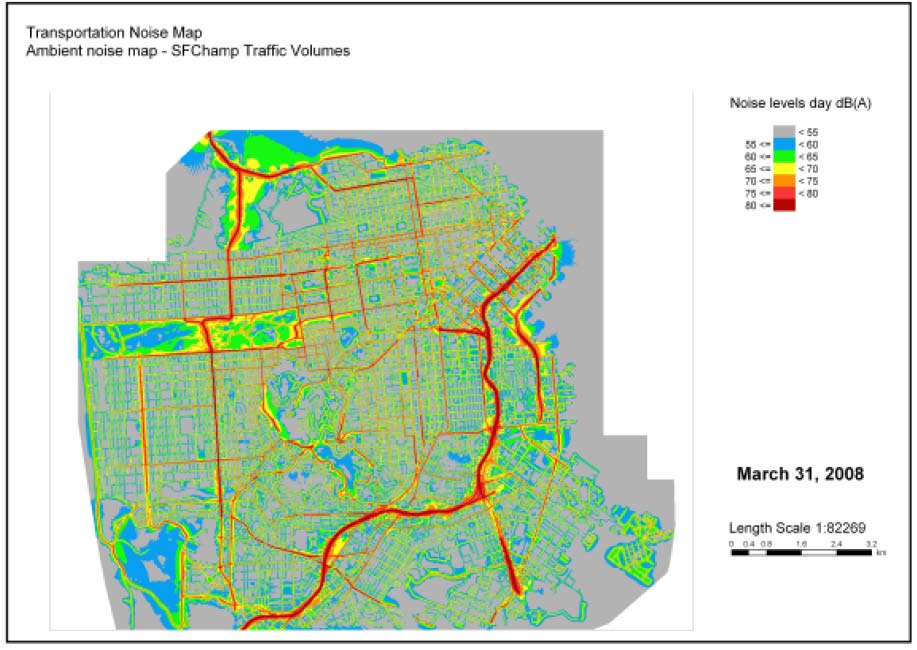

San Francisco, California

Initially developed to test early warning sirens, San Francisco’s new noise map was last updated in March 2008 and includes transportation and industrial noise sources.

Challenges

The advancement of noise mapping in the United States faces several challenges, most

notably:

• No enabling legislation. There is no national legislation or directive requiring

large communities to conduct noise mapping. Without this powerful incentive,

many communities will choose to concentrate their planning efforts in areas that

are required by law, such as transportation and air quality.

• TNM not suited for noise mapping. The U.S. Federal Highway

Administration’s “Traffic Noise Model,” the standard for traffic noise modeling

in the United States, is not appropriate for noise mapping. It is relatively difficult

to program in large areas, is slow, and has limited graphical output. Two

European noise mapping software developers are implementing the TNM

algorithms into their software, but they have not yet been approved for official use

in the United States.

• Not a priority. Noise planning is simply not a priority in many U.S. metropolitan

areas. While some cities are an exception, like San Francisco and Portland,

Oregon, quantitative planning tools are not common.

Opportunities

The United States has a wide array of data sources that is relatively easy to access and

use for noise mapping. These sources will allow for the accelerated implementation of

noise mapping once communities start to demand better planning. Three important

starting points are in place:

• Good traffic data exist. All Metropolitan Planning Organizations, which exist in

most urban areas with populations of 50,000 or more, have some type of

transportation demand model and traffic estimates for major roadways.

• Good GIS data exist. GIS data for terrain, land cover, and, in some areas,

buildings are common and usually available for free.

• Growing grassroots efforts. While there is no legislative initiative, individual

cities and counties are starting to take interest.

It remains to be seen whether legislation at the national level or continued local-level

involvement will ultimately drive the future of noise mapping in the United States and

provide the stimulus for an EU-style of integrating noise mapping into community

planning.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Jose Alicea-Pou of the Environmental Quality Board of Puerto Rico for his contributions of the noise map. In addition, thanks go to Bennett Brooks of Brooks Acoustics Corp., Tom Rivard of the San Francisco Department of Health, Paul Van Orden of the City of Portland, Julie Wiebusch of The Greenbush Group, Inc., and David Dubbink of California Polytechnic State University.