Perceptual Adaptation to Foreign-Accented English

Ann R. Bradlow - abradlow@northwestern.edu

Tessa Bent, Melissa Baese-Berk and Beverly A. Wright

Northwestern University, Department of Linguistics

2016 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208

Popular version of paper 4aSC2

Presented Thursday morning, October 29, 2009

158th ASA Meeting, San Antonio, TX

Introduction

Many conversations across the globe today take place between interlocutors who do not share a mother tongue, or who, for various socio-political reasons, communicate in a language other than their shared mother tongue. In the case of English, non-native speakers have come to outnumber native speakers, and interactions in English increasingly do not include native speakers at all. Thus, much of the English in use today is foreign-accented English.

Foreign-accented English presents a challenge for accurate and efficient speech communication between native and non-native speakers because it differs quite dramatically from the speech that native speakers are used to hearing. If we know exactly how and why foreign-accented speech differs from unaccented speech, we may ultimately be able to figure out a way to enhance English speech communication in a global context by training the talkers, by computer manipulation and/or by training the listeners.

In our work we are trying to understand the conditions that promote listener adaptation to foreign-accented speech. Our experience tells us that the more we interact with a particular foreign-accented speaker, the better we get at understanding his or her speech. For example, students in classes with foreign-accented professors or teaching assistants, typically adjust to the foreign-accent over the course of the academic term. Therefore, we have good reason to believe that listener training may be an effective approach to the goal of enhancing speech communication across native and non-native English speakers. However, how can we help listeners adapt to foreign-accented speech in a fast and efficient manner?

Our approach to this question builds on our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie foreign-accented speech production in relation to unaccented speech production.

Three sources of systematic (rather than random) foreign-accented speech deviations

Foreign-accented speech deviates from the unaccented norms for three main reasons.

(1) Universal problems of foreign language production

Speaking a foreign language is hard regardless of the source and target languages. Therefore, foreign-accented speech in all languages will exhibit certain consistent features. For example, English learners of French will typically produce relatively slow French speech, Japanese learners of English will typically produce relatively slow English speech, German learners of Italian will typically produce relatively slow Italian speech, and so on. This source of foreign-accented speech deviation results in commonalities (e.g. slow speech rate) across all foreign accents regardless of the native and foreign languages involved.

(2) Source- target language interactions

It is hard to "turn off the patterns of speech production that you learn for your native language. Therefore, foreign-accented speech typically exhibits features of the speaker's native language that are incompatible with the target language. For example, since no words in Spanish begin with /sp/, Spanish learners of English frequently mispronounce English words that begin with /sp/ ("special" gets pronounced as "especial," etc.). And, since English has only one "r" sound while Spanish has a distinction between "r" and "rr", English learners of Spanish frequently have trouble producing two clearly distinct words for "pero" ("but") and "perro" ("dog"). This source of foreign-accented speech deviation results in commonalities across all speakers from a particular native language background when speaking a particular foreign language.

(3) Target language typological peculiarities

Some features of individual languages can be so rare across the languages of the world, that talkers from most other languages will have difficulty with this feature. For example, the English distinction between the vowels in 'beet' and 'bit' is unusual enough that foreign-accented English speakers from many different native languages have a hard time distinguishing these words (and many others like these pairs: feet-fit, seat-sit, meet-mitt, leak-lick) This source of foreign-accented speech deviation results in commonalities across talkers from many different native language backgrounds when speaking a particular target language.

Importantly, each of these three sources of deviation results in systematic, rather than random, variability of foreign-accented speech relative to unaccented speech.

Listener adaptation to the systematic deviance of foreign-accented speech

Precisely because foreign-accented speech deviates systematically rather than randomly from unaccented speech, listeners should be able to adapt to foreign-accented speech.

Accordingly, our experiments investigated three levels of listener adaption to foreign-accented English:

Talker-specific adaptation: adaptation to an individual talker after exposure to the speech of that talker

Talker-independent accent-specific adaptation: adaptation to an accent as it extends over a group of talkers from the same native language background after exposure to multiple talkers of that accent

Accent-independent adaptation: adaptation to foreign-accented English in general after exposure to talkers from several different native language backgrounds

Here's what the participants did:

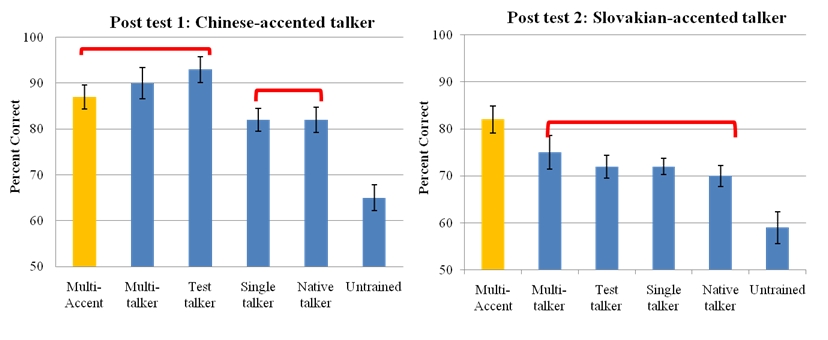

Native English speakers participated in two one-hour training sessions over two days. The training consisted of a dictation task with simple English sentences. Participants were instructed to listen to each sentence and to write down as much of the sentence as they could. The sentences were presented as recordings over headphones. At the end of the two training sessions, all participants were tested on Post-test 1, a dictation test with recordings of a Chinese-accented English talker, and Post-test 2, a dictation test with recordings of a Slovakian-accented English talker. We then compared performance on these post-tests, in terms of the number of words correctly transcribed, across groups of listeners who were trained on (a) a single Chinese-accented talker, (b) multiple Chinese-accented talkers, or (c) 5 different foreign-accented English talkers from 5 different native language backgrounds (Chinese, Romanian, Hindi, Thai, Korean, and Chinese).

Here's what we found:

Talker-dependent adaptation: Listeners could quite easily adapt to the speech of an individual Chinese-accented talker provided that they were give sufficient exposure to that talker's speech (see the "Test talker column in the left panel of the figure below). However, training on a single Chinese-accented talker who was not the test talker (the "Single talker column in the figure) did not help the listeners understand another Chinese-accented talker or a Slovakian-accented talker. This single-talker training resulted in talker-specific adaptation.

Talker-independent adaptation: Listeners who were exposed to five talkers of Chinese-accented English (the "Multi-talker column in the figure) were better able to understand the speech of a sixth talker than listeners who had no training (the "Untrained column in the figure) or who were trained on the speech of a single Chinese-accented talker who was not the test talker (the "Single talker column in the figure). However, this multiple-talker training did not help the listeners understand an entirely different foreign-accent, namely Slovakian-accented English. This multi-talker training resulted in talker-independent, accent-specific adaptation.

Accent-independent adaptation: Listeners who were exposed to foreign-accented English by five talkers from different native language backgrounds (Chinese, Romanian, Hindi, Thai, Korean, and Chinese, the "Multi-accent column in the figure)) were better able to understand the speech of both a trained accent (i.e. Chinese-accented English) and the speech of an untrained accent (i.e. Slovakian-accented English). This multi-accent training resulted in accent-independent adaptation.

Fig 1. Performance on the two post tests by listeners in the various training groups. Red bars connect columns that are not significantly different. Multi-accent = trained on 5 different accents, Multi-talker = trained on 5 talkers of Chinese-accented English; Test talker = trained on the Chinese-accented English talker in Post-test 1; Single talker = trained on a single Chinese-accented English talker who was not the talker in Post-test 1; Native talker = a control group trained on native-accented English; Untrained = no training prior to Post-tests 1 and 2.

We also found that adaptation to foreign-accented English can occur even with a training procedure that does not always involve active participation of the listener. We observed talker-specific, talker-independent and accent-independent adaptation even when the listeners did a decoding puzzle while hearing foreign-accented speech in the background. This is exciting because it suggests that we may be able to help listeners improve their ability to understand foreign-accented speech by just playing foreign-accented speech to them while they go about their daily lives.

Taken together, our findings suggest that listeners are very flexible in their processing of spoken language. Moreover, a highly efficient way to train listeners to better understand foreign-accented English may be to expose them to multiple accents, and at least some of this exposure can be while they are engaged in other tasks.