iPod Preferred Listening Levels for College Students

Edward L. Goshorn - edward.goshorn@usm.edu

Kathryn Jade White, Brett E. Kemker

University of Southern Mississippi

Psychoacoustics Laboratory

118 College Dr #5092

Hattiesburg, MS 39406-0001

Popular version of paper 2pNS9

Presented Tuesday morning, October 27

158th ASA Meeting, San Antonio, TX

Portable personal music devices (PPMD) such as the Apple iPod have recently grown in popularity. Sales of iPod-like devices have exceeded 100 million worldwide. These devices are typically used with small ear buds inserted into the users ear canal, thus assuring a high degree of privacy relative to content and loudness. This study addressed loudness concerns. Previous studies show that a PPMD may reach loudness levels as high as 130 decibels. Loudness levels greater than 85 decibels on an 8-hour daily basis have been shown to be hazardous to human hearing. Thus, there is concern that users may set their devices to listening levels that will eventually cause permanent hearing loss. Conventionally, listening levels of personal radios, etc., could be monitored by authority figures such as parents, teachers, employers/supervisors, or significant others. However, the privacy nature of PPMDs permits the user to listen at hazardous levels without the knowledge of monitoring individuals. Thus, there is concern that PPMD users will listen at loudness levels that are known to cause permanent hearing loss.

This study investigated the levels at which college-age individuals set their PPMDs when listening to a popular tune. Subjects were instructed to play the tune at their preferred listening level. The tune played by all subjects is a well-known recording by a popular performing artist (Summer of 69, Brian Adams). The tunes loudness at the subjects eardrum was measured at the same point in the tune for each subject. Loudness measures were taken with a soft flexible microphone extension that led to a computer and software analyzer. Subsequently, measures were taken of an uploaded steady-state broadband noise .wav file at the identical user setting to verify accuracy of measured music levels.

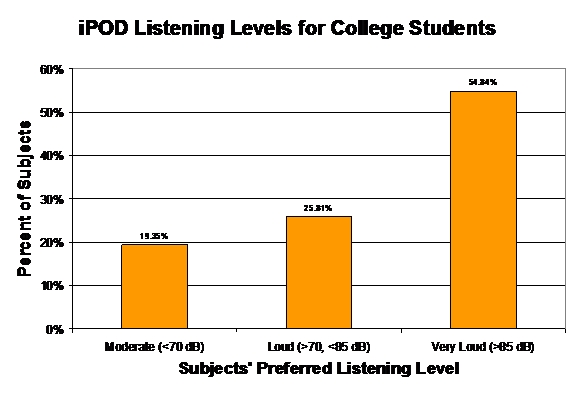

Results show that a majority of the college students used in this study set their devices at preferred listening levels that are sufficiently loud to gradually and eventually cause permanent hearing loss. Fifty- five percent set their devices to very loud levels (greater than 85 decibels). Twenty six percent set their devices to loud levels (greater than 70 but less than 85 decibels). Nineteen percent set their devices to moderate levels (less than 70 decibels).

Figure 1. iPOD listening levels for college students

When preference for music genre is considered, subjects who preferred Country and Pop had the highest average settings (89 and 88 decibels, respectively) but Rap and Rock enthusiasts had the highest individual settings with Rap at 100 decibels and Rock at a booming 107 decibels. The average loudness levels and individual subject loudness levels in decibels are shown in the table below for each subjects preferred genre.

|

Subjects Preferred Genre |

Number of Subjects |

Average Loudness Level at Subjects Eardrums |

Highest Individual Loudness Level at a Subjects Eardrum |

|

Country |

5 |

89 |

99 |

|

Other |

4 |

74 |

93 |

|

Pop |

6 |

88 |

98 |

|

Rap |

5 |

75 |

100 |

|

Rock |

11 |

84 |

107 |

No subjects had significant hearing loss, but it should be noted that these subjects had owned PPMDs less than three years and have not, thus far, had enough exposure to cause permanent hearing loss. Hearing loss due to loud sounds is typically very gradual over a period of years and occurs in such a way that the individual does not notice the loss of hearing until it advances to a stage at which perception of conversational speech is significantly impaired or tinnitus becomes quite noticeable.

Finally, the measured decibel levels for music were not significantly different from measured decibel levels for white noise. Thus, white noise, a more stable signal over time, is an acceptable substitute for a music file. The advantage in using a white noise file is that music may vary greatly in intensity from moment to moment and yield misrepresentative data.

METHOD

Subjects: Thirty-one young college-age subjects, 17 males and 14 females, volunteered. The average age was 21 years and ranged from 18 to 23 years.

PPMD Measures: A flexible plastic tube leading to a microphone was placed in the subjects ear canal at a depth of 20 mm. Each subject used his or her own PPMD with the ear bud inserted into the subjects preferred ear. Subjects were instructed to play a tune that was downloaded by the investigators to their PPMD. The point of measure for each subject occurred at 1 minute 10 seconds into the tune, giving the subject time and opportunity to adjust the PPMD to their preferred listening level. A Frye-Fonix Model 7000 real ear measurement system captured the sound pressure level and spectrum of the tune at the moment of measure. No adjustments to the PPMD were allowed once the measure was taken for loudness level of the tune. The PPMD was then set to play a file containing a steady-state broad band (white) noise. Measures of SPL and spectrum were then obtained for the broad band noise.

Hearing Capability Measures: Each subject had a hearing test for pure tone thresholds at octave intervals from 250 through 8000 Hz. No subject had significant hearing impairment.

Survey: Each subject completed a survey pertaining to demographics and preferences for type of music, daily hours of listening, and duration of PPMD ownership.

DISCUSSION

These findings suggests that college age PPMD users may set their device to listening levels that are hazardous to human hearing if left at such levels for prolonged periods. This study used young normal hearing subjects who were either new owners or had owned PPMDs for three or fewer years. That is, the subjects in this study have not had the opportunity to use their devices at the high-intensity levels and for the prolonged intervals that are associated with permanent noise-induced hearing loss.

A second significant finding from this project is that downloaded .wav broadband noise files are a suitable and stable measuring substitute for music files that may vary greatly from moment to moment and thus may yield unreliable measures.