Using Acoustics to Examine the Possible Impacts of Trawling on Marine Forage Fish

Jason D. Stockwell - jstockwell@gmri.org

Gulf of Maine Research Institute

350 Commercial Street

Portland, ME 04101

Thomas C. Weber - weber@ccom.unh.ed

University of New Hampshire

Center for Coastal Ocean Mapping

24 Colovos Road

Durham, NH 03824

J. Michael Jech - Michael.jech@noaa.gov

National Marine Fisheries Service

Northeast Fisheries Science Center

166 Water Street

Woods Hole, MA 02543

Adam J. Baukus - abaukus@gmri.org

Gulf of Maine Research Institute

350 Commercial Street

Portland, ME 04101

Daniel J. Salerno - dsalerno@gmri.org

Gulf of Maine Research Institute

350 Commercial Street

Portland, ME 04101

Popular version of paper 3aAO3

Presented Wednesday morning, October 28, 2009

158th ASA Meeting, San Antonio, TX

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) has launched a study using acoustic systems to assess the impact of fishing on Atlantic herring populations. The results will shed light on long-debated questions about the potential of fishing practices to negatively affect other species, such as Atlantic bluefin tuna and seabirds that come into the Gulf of Maine to feed on large schools of herring.

Figure 1. A school of Atlantic herring.

Fishing provides an important source of protein for a hungry world as well as jobs in many coastal communities, but some practices may cause damage to the marine environment. Depletion of fish populations worldwide from overfishing is well documented. Trawling heavy fishing gear on the bottom of the ocean can ruin habitat, and ghost gear (lost or abandoned fishing gear in the ocean) is a continual source of mortality and injury for marine life. In the Gulf of Maine, the potential impacts of midwater trawling -- in which a net that is towed through the water column to catch Atlantic herring -- has been the source of a bitter controversy within and among fishing industries, conservation and environmental organizations, and other stakeholders.

Figure 2. Midwater trawler fishing for herring.

Opponents to midwater trawling argue that such fishing practices disrupt large schools of herring that are essential food for large predators and provide other ecosystem functions. Trawling may have a negative impact on the environment and other consumptive (e.g., recreational anglers, tuna industry) and non-consumptive (e.g., ecotourism) user groups.

Proponents contend that impacts of midwater trawling are minimal but sensationalized.

Unfortunately, knowing exactly what is going on beneath the oceans surface can be challenging.

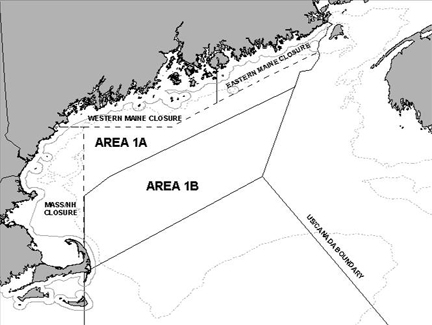

Currently there is not enough scientific data to say with certainty how herring behave in response to midwater trawling. However, as a result of heavy political pressure, the New England Fishery Management Council narrowly voted to ban midwater trawlers from the most productive and accessible management zone from June 1 to September 30 starting in 2007.

Figure 3. Midwater trawlers are banned from Area 1A.

Without better science, it will be difficult to assess whether this ban had the intended impact.

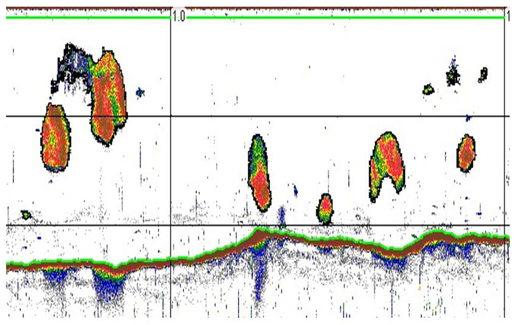

GMRI scientists believe it is possible to use sound to capture a three dimensional image of herring and resolve this controversy. We launched a pilot project to test whether combining horizontal- and downward-looking acoustic systems (a sophisticated fish finder) can make it possible to compare changes in herring aggregations before and after midwater trawling operations.

Figure 4. Image of herring schools from a downward-looking acoustic system.

In our presentation, we will present preliminary analyses from data collected in fall 2008 and summer 2009. Final data collections will be completed this fall.

Results from this pilot study are a first step to a much broader assessment of the impacts of midwater trawling on prey fish species that are critical to marine food webs. Our goal is to develop and evaluate an acoustic toolbox to address questions of fishing impacts in the pelagic environmentthe area located within the water column (as opposed to the ocean floor). The study design will enable us to evaluate how large schools change immediately after fishing. Perhaps more importantly, it will provide a foundation to examine the potential impacts of the activities of an entire fishing fleet on the ocean environment.