Depth-profiling Ambient Noise in the Deepest Oceans

David R. Barclay - dbarclay@mpl.ucsd.edu

Fernando

Simonet - nando@mpl.ucsd.edu

Michael J.

Buckingham - mbuckingham@ucsd.edu

Marine Physical Laboratory,

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

University of California, San

Diego

9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA

92093-0238, USA

Popular version of paper 1pUW4

Presented Monday afternoon, April

19, 2010

159th ASA meeting, Baltimore, MD

In 1951, during a survey of the

Mariana Trench near Guam, the British Royal Navy ship HMS Challenger identified the deepest known point in the ocean,

recording a depth of 10,911 meters (35,797 feet) at a position near 11˚

22 N 142˚ 36 E. Known as the Challenger Deep, the sea bed at this

location is as far beneath the sea surface as commercial jet aircraft fly above

it. Few descents to the bottom of the Challenger Deep have been attempted, and

only one manned submersible has ever reached the greatest depth, the bathyscaph

Trieste on 23 January 1960 with

Jacques Picard and US Navy Lieutenant (as he was then) Don Walsh on board.

Some fifty years on, it remains a

fact that almost nothing is known about the greatest ocean depths, not least

because of the enormous pressure that any exploratory vehicle must withstand in

order to survive the deepest dives: every 10 meters down is equivalent to an

increase in pressure of one atmosphere, which equates to approximately 1,100

atmospheres at the bottom of the Challenger Deep. By comparison, a space craft

operates in a benign environment, having to contend with a pressure of just one

atmosphere!

The ocean is an acoustically

noisy environment, with sound created by wind-driven waves on the sea surface,

by various seismic events including earthquakes and volcanoes, by marine

mammals and other sea creatures, and by anthropogenic activities associated

with shipping, along with offshore surveying and drilling for hydrocarbons.

Although the characteristics of near-surface ambient noise have been fairly

thoroughly investigated, comparatively little is known about the nature of the

ambient sound field at greater depths, and especially at depths below 6,000

meters. To probe these extreme regions, we have developed Deep Sound, an untethered

instrument platform with the capability of descending to (and returning from)

the bottom of the oceans deepest trenches.

Figure

1. An early

version of Deep Sound, photographed during a tethered engineering test.

Deep Sound, illustrated in Fig.1,

is designed to free-fall from the sea surface to a pre-assigned depth, at which

point a burn wire releases a drop weight, allowing the system to return to the

surface under buoyancy. The descent and ascent rates are the same at 0.6 m/s,

corresponding to a round-trip travel time to the bottom of the Challenger Deep

of just over 10 hours. A critically important component of Deep Sound is a

Vitrovex glass sphere, comprised of two hemispheres, with an external diameter

of 43.2 cm. The sphere houses a pack of lithium-ion batteries, of the type

found in modern lap-top computers, and a suite of microprocessor-controlled

electronics for data acquisition, data storage, power management and system

control. Outside the sphere, several hydrophones (underwater microphones) are

arranged in vertical and horizontal configurations, and a

conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) probe returns environmental data from

which the speed of sound as a function of depth is computed. Motion sensors

continuously monitor the pitch, roll and yaw of the system, allowing advection

due to local current flow to be monitored.

All the data acquired during a

deployment of Deep Sound are stored on-board in solid-state memory. It is

therefore imperative that the drop weight releases, enabling the system to

return safely to the surface with the data. A sequence of fail-safe mechanisms

has been integrated into the system, designed to ensure that the burn wire is

indeed triggered even though the pre-assigned depth may not have been

reached. Recovery of the system is

facilitated by three antennas: a radio beacon, an Argos (GPS) beacon and a

xenon high-intensity strobe light. Once Deep Sound is back on board ship, the

data are downloaded via a wireless link or through hard-wire connectors

penetrating the sphere. Other penetrators allow the batteries to be recharged

without separating the hemispheres.

Each of the hydrophones has a

bandwidth of 30 kHz and is calibrated over a substantial depth range. The

motion of the hydrophones through the water induces a local turbulent flow

field, which in turn creates low-frequency (below a few hundred Hertz)

interference in the acoustic recordings. To reduce the effects of this flow

noise, each hydrophone is fitted with an open-pore-foam flow shield, which in

effect keeps the turbulent pressure fluctuations away from the active surface

of the sensor.

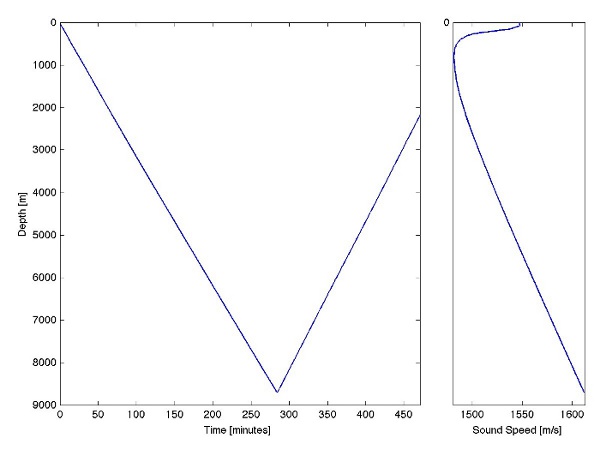

Figure

2. Depth versus

time profile for one of the Deep Sound deployments in the Mariana Trench.

In May 2009, Deep Sound was

deployed on three occasions in the Philippine Sea, to depths of 5,100, 5,500

and 6,000 meters. Two further deployments were made in November 2009, in the

Mariana Trench, both to a depth of 9,000 meters. The system was successfully

recovered after all these deployments and complete data sets were downloaded

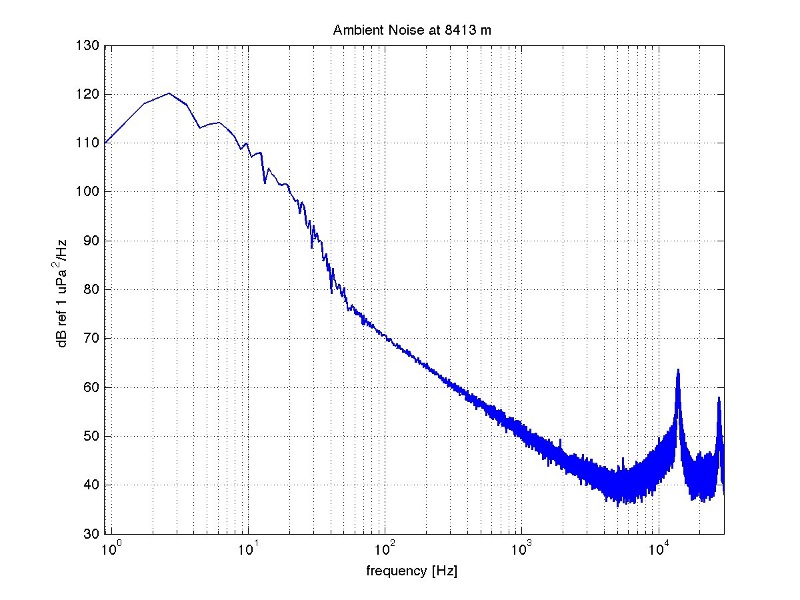

from the onboard memory. Fig. 2 shows an example from the Mariana Trench of a

depth-versus-time profile, along with the sound speed profiles that were

measured during the descent and ascent; and an ambient noise spectrum taken at

a depth of 8,413 meters at the same location is shown in Fig. 3. This noise

spectrum is notable for its smoothness over much of the spectral range, which

is testimony to the effectiveness of the flow shield on the hydrophone. By

combining the outputs from two vertically aligned hydrophones, it is possible

to obtain the vertical coherence of the noise, which provides a measure of the

directionality of the noise in the vertical. Such information helps in

understanding the effect of the sound speed profile on the spatial and temporal

properties of the ambient noise field.

Figure

3. Ambient noise

spectrum from a depth of 8,413 m in the Mariana Trench.

The ultimate challenge for Deep

Sound is, of course, the Challenger Deep at the southern end of the Mariana

Trench. To meet the demands of descending to such a great depth, a new version

of Deep Sound is currently being developed with an enhanced depth rating and an

extended sensor suite, but still retaining a Vitrovex sphere as the pressure

vessel housing the electronics. In the late summer of 2010, we plan to deploy

the new system to a depth of almost 11,000 meters, to the bottom of the

Challenger Deep. If successful, it will return with continuous acoustic and

environmental recordings taken from the surface to the bottom of the deepest

known part of the Earths oceans. (Research supported by the Office of Naval

Research)