Ambient Noise Levels and Reverberation Times in

Megan

Noelle Lucus

Brett

E. Kemker

Dept.

of Speech and Hearing Sciences, Psychoacoustics Laboratory

Univ.

of

118

College Dr. #5092

Hattiesburg,

MS 39406-0001

Popular

version of paper 2PAAa11

Presented

Tuesday afternoon, Apr 20, 2010

159th

ASA Meeting,

Poor

acoustics can make listening difficult. This is true for all settings but is especially

important in elementary school classrooms. If a child cant hear or understand the

teacher, learning is diminished. Further,

students who enter a classroom with a disadvantage for listening, such as

hearing loss, will have even more difficulty understanding in a classroom with

poor acoustics.

A

major contributing factor to this problem is that classroom acoustics are not

taken into account during the planning stages of construction. As a result, schools are constructed near

busy highways and airports and may have noisy heating and air conditioning (HVAC)

units. These conditions may produce an intrusive background noise level, which not

only distracts the student but requires the teacher to raise his or her voice

in order to be heard, a practice that can lead to vocal problems.

Therefore,

every classroom should be evaluated to see if acoustic conditions are conducive

to learning. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI S12.60-2002) has

published acoustical criteria guidelines for appropriate background noise

levels and reverberation times for schools. Background noise and reverberation time can

interfere with ones ability to understand speech in two different ways. First, background noise, if sufficiently

high, can directly override speech sounds and make them inaudible or

unrecognizable. Second, even in a quiet

room, reverberation time can interfere with ones ability to understand speech. The interference is due to the presence of

reflected speech sounds (echoes) that arrive at the ear later in time than the

same speech sounds that take a direct path to the ear. This reverberation effect is sometimes

described as smearing of speech sounds. Reverberation time is defined as the time it

takes for a sound to decrease in level by 60 decibels. The more highly-reflective surfaces a room

has, the longer a sound will continue to bounce around even after the source of

the sound has stopped. Thus reverberation

can also contribute to the overall background noise level. Noise and reverberation can act in isolation

or jointly to reduce the ability to understand speech.

Compliance

with the ANSI standard is voluntary, so it is the responsibility of each school

district to determine if its classrooms meet the standard. Thus, the purpose of this study was to

determine if a sample of elementary public school classrooms in the

Two

acoustical measures (background noise level and reverberation time) were taken

in each room. Both measures were

obtained with an Audix TR-40 measuring microphone

whose output led to SpectraPLUS Version 5 software. This computerized system was used to record and

analyze the ambient noise and to measure reverberation time. Three samples of each measure were taken in

each room to assure accuracy of the measures.

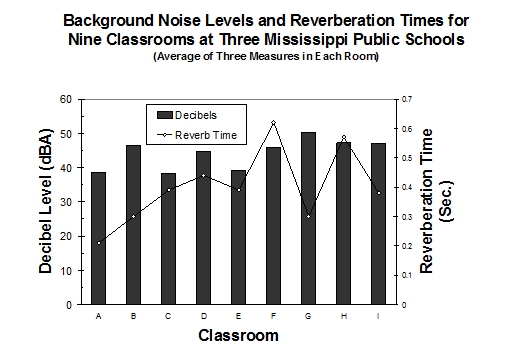

The

acoustical measurement findings from this study are summarized in the figure

below. Average background decibel noise levels

can be read from the scale on the left. Average

reverberation times can be read from the scale on the right. Each point is the average of three

measures. The variability of these

measures was small as reflected by standard deviations of 1.1 decibels for

noise and .13 seconds for reverberation times.

Figure 1. Summary of acoustical measures taken at

three Mississippi Schools

The

ANSI standard for school classroom background noise is 35 decibels (A-weighted)

and .60 seconds for reverberation time in rooms smaller than 10,000 cubic

feet. We found that no classrooms met

the ANSI standard for background noise level.

Average noise levels for each room varied from 38 to 50 decibels

(A-weighted). A spectrum analysis

showed that most of the noise was in the low frequency range, a finding consistent

with previous studies of school classroom acoustics. Eight of nine classrooms met the ANSI

standard for reverberation time, ranging from .21 to .62 seconds. All nine classrooms were less than 10,000

cubic feet.

While

all but one classroom met the ANSI recommended reverberation time, none met the

standard for background noise level and thus these classrooms do not have

acoustical characteristics that are optimum for learning. The negative impact of background noise on

the learning process is well-documented. There is ample evidence from previous research

that classroom background noise levels that exceed 35 decibels are detrimental

to hearing and understanding speech and thus diminish the capacity for learning. Therefore, acoustic modifications or

classroom accommodations for teachers and/or students may be necessary for all the

classrooms measured in this study.

Once

a classroom has been identified as having poor acoustics one must consider the

remediation necessary to either comply with the standard or to improve

capability for learning. It is important

to remember that the overall goal is to improve the speech-to-noise ratio so

that children in the classroom can hear and understand the teacher. Previous studies show that a teachers speech

needs to be at least 15 decibels above the noise (15 decibel speech-to-noise

ratio). This condition is achieved when

a teacher speaks at an average conversational level when the background noise

level is below 35 decibels. However, in

the classrooms measured in this study the minimum 15 decibel speech-to-noise

ratio is not met due to the background noise levels exceeding 35 decibels.

There

are at least two approaches one may take in dealing with high background noise levels

that interfere with speech. The speech signal can be increased or the noise

level can be decreased. Thus, the first option to consider for improving

the speech-to-noise ratio is to increase the speech level. It is not sufficient to merely request the

teacher to speak louder as this can result in physiological damage to the

larynx. A common remedy is to have the

teacher use an amplification system.

Such a system is similar to a public address system in which the teacher

wears a microphone and his/her speech is routed to an amplifier. The amplified output is adjusted to present the

teachers speech at comfortably loud levels.

Loudspeakers are distributed around the classroom in such a way as to

enable all students in the classroom to hear at an acceptable speech-to-noise

ratio. Although this approach may

resolve the background noise problem for one classroom, a teachers amplified

speech may contribute to the noise level for classrooms nearby. Another

possibility is to identify students who are known to be at risk to noise and to

have these students wear personal electronic systems that receive speech sounds

directly from the teacher. Again, the

teacher wears a microphone but the output from the microphone in this case is

transmitted via frequency modulated (FM) wireless technology to a students

personal FM receiver with private earphones for each child. In this way, the child can adjust his/her FM receiver

to a comfortable listening level. With

FM transmitters, different frequency-transmitter channels may be used in each

classroom to avoid interference with FM systems in other classrooms. Also, FM systems would not contribute to noise

levels in adjacent classrooms. Some of

the disadvantages to FM systems are that they are expensive and require

professional expertise to assure that all students who use an FM system have it

set properly and that it is in good operating condition every day.

The

second option to consider in dealing with high background noise is to decrease

the background noise level. The literature regarding classroom acoustics

consistently identifies HVAC units as a chief source of background noise. The temporal and acoustic characteristics of

the noise measured in this study indicate that the primary noise source is the

HVAC system. Unfortunately, it is so

expensive to replace noisy HVAC systems with quiet ones that this solution is

rarely chosen. Therefore, administrators

should consider the noise impact of HVAC systems at the planning stage. Other

known noise sources such as highway traffic and airport noise may be addressed

through legislative avenues. Future school construction must take

acoustical characteristics into full consideration. It should become common practice to include

acoustical standards in contractors bids for school construction or in modification

to existing structures. The overall school location and classroom location

within the school are other important noise-contributing factors to consider

prior to construction. School boards

should consult acoustical experts for advice.

Our

findings indicate that the classrooms measured in this study are not optimal for

learning because none met the ANSI guideline for background noise. The primary source of the background noise in

each classroom was the HVAC system. While

improvements in listening are possible by means of amplification systems for

teachers and personal FM transmitters/receivers for select students, these

remedies are not always practical and often create other problems. It is obvious that if schools are going to

meet the ANSI recommended guidelines, then acoustical characteristics of classrooms

must be considered paramount by administrators when planning future construction.

Although

compliance with acoustical standards is not mandatory, we strongly recommend

the following:

1. We urge school districts to conduct acoustic

assessments to determine if their classrooms meet the ANSI standard. This recommendation is even more appropriate

for school systems that have high failure or drop-out rates.

2. If ANSI S12.60-2002 guidelines are not met,

then efforts should be made to either alter the acoustical characteristics to

meet the standard or provide accommodations for teachers and students to

provide an optimal acoustical learning environment until schools that meet the

standard can be built.

3. Future school construction must include

acoustical standards that meet ANSI guidelines and are known to be conducive to

learning.

4. School boards and administrators should seek

advice from acoustical consultants prior to beginning new construction or making

modifications to existing structures.