Adrienne B. Hancock hancock@gwu.edu

Rachael M. Harrington rharrin1@gwu.edu

James Mahshie jmahshie@gwu.edu

Alicia Lennon atlennon@gwu.edu

George Washington University

Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences

2115 G Street NW, Suite 201

Washington, DC 20052

Popular version of paper 1a2b3c

Presented Wednesday morning, May 25, 2011

161st ASA Meeting, Seattle, Wash.

Perceptual judgments about a person’s gender are formed quickly and are strongly influenced by that person’s voice and communication. Transgender (TG) individuals make considerable efforts to portray themselves in a way that ensures others perceive them as their desired gender. If they fail to do so, the social, occupational, and mental health ramifications can be dire. A speech-language pathologist has the expertise to provide voice and communication therapy to enable the TG individual to present a gender consistent with their personal gender identity. Many TG people enter therapy with a common complaint: “People view me as a woman until I open my mouth and a deep, gruff voice comes out”.

Early transgender voice therapy was limited to changing vocal pitch – at first aiming for the typical values of the desired gender and more recently aiming for more feasible targets of pitch within a “gender-neutral range” established by perceptual research. Twenty years later, research is discovering that pitch may be a major influence in gender perception, but is almost certainly not the only influence. There is very little data about how a male larynx can achieve a feminine voice. Acoustic and aerodynamic data are needed to describe how the vocal mechanism of a transgender person operates to achieve desired gender perception.

Acoustic and aerodynamic measures of voice production were collected for comparison between 10 male-to-female (MtF) transgender, 10 male and 10 female speakers. Several of these measures are established in the research literature as different for male and female speakers. It was hypothesized that values for MtF speakers would be between the male and female values approaching the values of their desired gender group, or perhaps even achieving the female values. Previous research has found this pattern for voice pitch. This study investigated:

Most of these measures have never been reported for TG voice.

Vocal fold vibration is not quite like guitar strings. Rather, as air flows upward from the lungs through the larynx toward the mouth, it passes through a space (called the glottis) shaped by the two vocal folds. During voicing the vocal folds are in a continuous cycle of opening and closing the glottis from the bottom of the glottis to the top of the glottis. This study’s data were consistent with previous reports; compared to males, females spend proportionally more time in a cycle with the glottis open than closed. This is referred to as the Open Quotient. The Open Quotient for MtF speakers in this study was significantly different from the male group, reaching values of female speakers.

There are a few ways to adjust vocal fold physiology to increase the Open Quotient. Both the open and closed phases of the cycle can be further divided into opening and closing segments within the phases. Previous reports of male and female speakers suggested that most of the closing of the glottis is done during the closed phase of the cycle whereas for females most of the closing is done during the open phase of the cycle. This explains how females are able to achieve a longer Open Quotient than males, perhaps contributing to the breathier voice quality associated with females. Therefore it was predicted that the MtF would adjust the closing segments of vocal fold vibration to change from a male pattern toward a female pattern. However, the data indicated that the first part of the open phase – when the glottis is opening – is the segment that MtF speakers increased in order to achieve an Open Quotient like females. It remains unclear why this pattern – unique from males and females- is adopted for making a biologically male larynx achieve a female voice quality but this finding may shift the traditional paradigm accepted in therapy, which has been for the individual to simply mimic the patterns of the desired gender group.

The driving force of vocal fold vibration is air flowing up from the lungs. The amount of air pressure used to initiate vibration was similar across our three groups, but the peak airflow during voicing was significantly greater for male compared to female speakers, with MtF values falling between those of male and females. More detailed measures indicate the difference stems from the controlled portion of vocal fold vibration (AC flow), rather than the uncontrolled minimal air leakage (DC flow). These differences between males and female speakers are consistent with previous research. Only one other study has examined these measures in MtF speakers, and this MtF group did not replicate those findings. Whereas in this study the MtF group’s values were between the male and female groups for these airflow measures, Gorham-Rowan and Morris’ (2005) 13 MtF participants produced airflow values greater than either group.

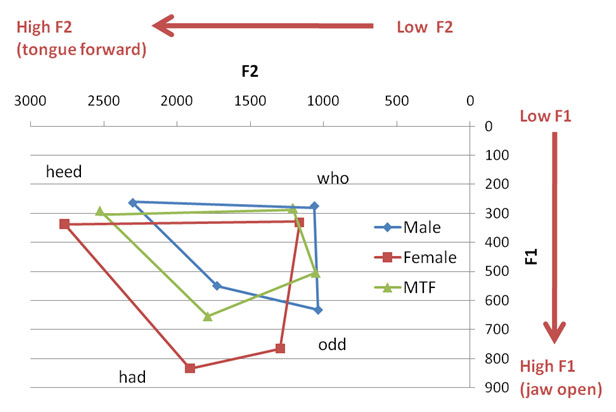

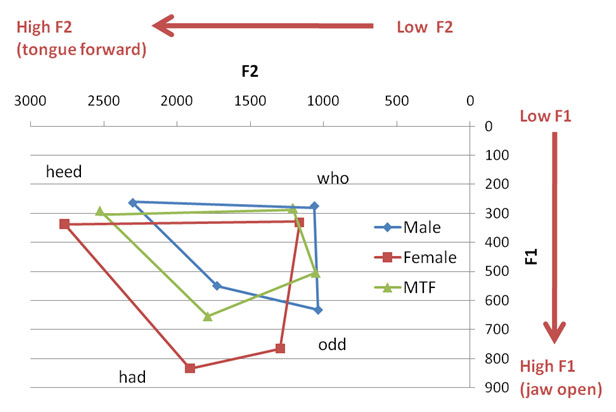

The acoustic signal of the voice resonates in the mouth; the sound that comes out depends on the shape of the oral cavity. Four vowels with the most different mouth shape were used in this study: “eee” (heed), “aah” (had), “oo” (who), “ahh” (odd). For each vowel, an acoustic formant is calculated using a spectrogram to determine F1, which relates to the openness of the jaw (compare “eat” and “at”), and F2, which relates to the lip shape and tongue forwardness (compare “eat” and “boot”). In figure 1, the data are plotted for comparison to the vowel quadrilateral commonly referred to in phonetic science. The male and female data from this study are similar to those reported in the literature: females have statistically significantly higher F1 and higher F2 values (i.e., more open jaw and forward tongue placement) compared to males. The MtF speakers fall between the two groups.

In summary, there are several components of MtF voice that appear to simply be shifting from male toward female values (i.e., airflow and mouth posture). However, the most detailed examination of the vocal fold movement at the source of the voice reveals a unique movement pattern unlike either female or male speakers. Research will continue to investigate how the transgender vocal tract can safely overcome constraints of biological anatomy and which parameters contribute most to listeners’ perceptions of gender.

Figure 1. Formant frequencies for male, female, and male-to-female transgender speakers.