Andrew John Wright – marinebrit@gmail.com; awr@dmu.dk

National Environmental Research Institute

Department for Arctic Environment

Aarhus University

Frederiksborgvej 399

DK-4000 Roskilde

Denmark &

Department of Environmental Science and Policy

George Mason University

4400 University Drive

Fairfax

Virginia 22030

USA

Popular version of paper 1pABa1

Presented Monday afternoon, May 23, 2011

161st ASA Meeting, Seattle, Wash.

INTRODUCTION

In many countries, projects involving construction or other modifications of the environment are required to conduct environmental impact assessments to identify the environmental costs of such activities. In general, cumulative impact assessments (CIAs) are often mandatory as part of this analysis. These additional assessments are specifically intended to account for the overall impact on the environment of the project in question in combination with other previous human activity, and sometimes also foreseeable future development as well.

THE PROBLEM

While this is all fine in concept, aggregating the various impacts is actually quite difficult in practice. For example, establishing a ‘natural’ time of comparison in the environment (called a baseline) is not easy given the length of human influence in most areas of the world. Furthermore, the full scope and scale of impact is not always clear given than environmental consequences can move from one habitat to another (such as from the land into the ocean). Finally, many environmental impacts do not accumulate in a straight-forward way and it is not uncommon for two specific environmental consequences to result in an overall impact that is greater than the sum of their parts.

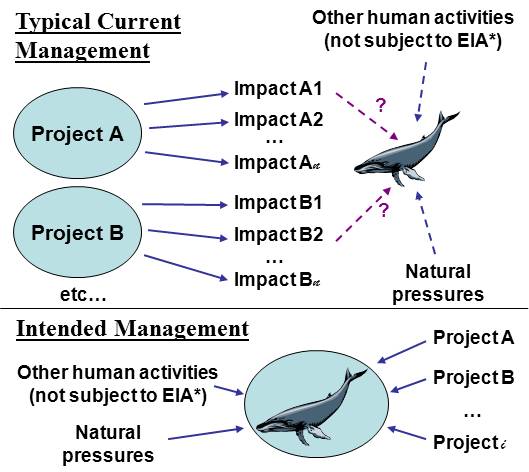

To complicate matters further, current management systems are almost invariably focused on each project in isolation, making it difficult to consider multiple projects together. Consequently, the intended legislative focus on the species, resource or environment is rather lost in the details of the implementing regulations.

Figure 1. A graphical representation of a typical current management system, above, and the more intended and ideal management system, below, which considers all of the possible influences on a population. *EIA = Environmental Impact Assessment. Images adapted, with permission, from originals by Lorne Greig, ESSA Technologies Ltd., Canada.

THE IDEA

To address this issue, Okeanos – Stiftung für das Meer (Foundation for the Sea) held an international, multi-disciplinary workshop in Monterey, California, in August 2009, bringing in participants from fields of expertise as diverse as botany and network physics. The intention was to consider: (1) if the building blocks currently available to managers for estimating human pressure on the environment could be used in the quantitative management of species; (2) how the reported consequences of exposure to noise in marine mammals could be combined with those relating to exposure to other human pressures; and (3) how the various consequences might interact within an individual and how this could be assessed. Despite the general lack of information on the biology of marine mammals due to the difficulty of studying them, participants felt at least the first two (and possibly also the third, to some extent) aspects of the problem could be realised in certain marine mammal populations, which could then be used as examples for informing management decisions in other species.

ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE

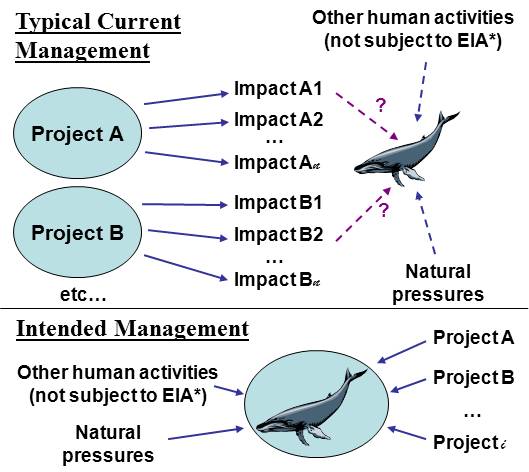

Before any real assessment of cumulative impacts can be undertaken, it is essential to first determine the location and extent of human influence in the environment. This may not be limited to the precise location of the human activity, but more often involves wider areas where, for example, noise or chemical pollution may travel to. Although this seems like an obvious step in the process, comprehensive outlines of all human influence are still quite rare. However, simply overlapping areas of exposure to various different human pressures will give managers a reasonable idea of which areas may be more heavily influenced by human activity, as well as those areas that are less impacted.

Figure 2. An example of overlaying various human activities and other pressures on the environment to produce an overall indication of possible environmental harm off the coast of California. Places with greater likely impact are in red, locations with low impact are in blue. Figure adapted from Figure 1, Halpern et al. 2009, with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

SPECIES EXPOSURE

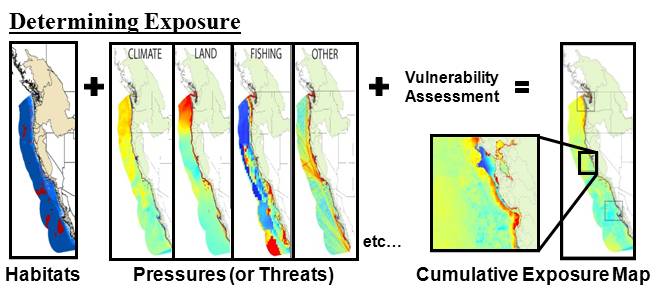

The next step, where data exist for the species of interest, would be to overlay the known distribution of the population on the combined exposure map. This would further help managers to determine areas where high human influence needs to be addressed, or relatively pristine places that could be protected, for the benefit of the species in question. In the case of animals, this step can be taken further still by accounting for movements of the population over time, which would lead to changes in their exposure to human influences.

Figure 3. Overlapping known population distributions with the exposure map can provide a reasonable indication of the extent to which a population of animals is likely to be influenced by human activity. Figure adapted from Figure 1, Halpern et al. 2009, with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

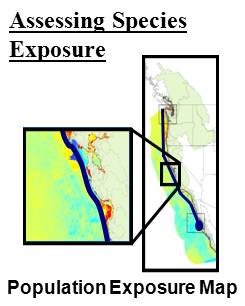

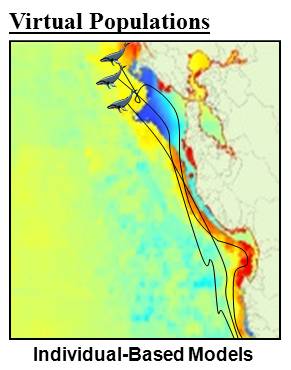

If enough data exist, individual-based models can be employed. These are computer simulations where virtual animals may roam through a landscape (or in this case a seascape) according to a number of rules that represent the known behaviour of animals in the wild. Such rules may include the seasonal drive to migrate or perhaps a preference for certain habitat types at different times of the day. Virtual populations can then move through their world accumulating (or perhaps avoiding) human influences. Ideally, if yet more data are available, the consequences of these exposures can then be estimated in terms of changes in survival and reproductive rates.

Figure 4. The general distribution of a population can be replaced with a computer model of a population of individuals. This allows those individual to move through the environment, allowing each animal to accumulate a unique history of exposure. Ideally, this could be combined with a further layer of modelling that would allow predict how the various consequences of this exposure history might combine and interact within each individual. Figure adapted from Figure 1, Halpern et al. 2009, with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

A VIRTUAL ANIMAL

If yet more information is available, it might even be possible to simulate the inner workings of an animal. Although extremely challenging to build, such a model would allow the consequences of exposure to the various human influences to interact in more realistic ways as they affect the simulated biological processes necessary for the survival of the animal. These simulated interactions could in some cases be verified against observations made in laboratories or the field. It is only at this level of detail that we can really begin to include concepts such as chronic stress and the consequences that are associated with it. At the workshop, this idea was developed only conceptually, as a full numerical exploration will require considerable effort if it is even possible at the present time.

TURNING THE TIDE

Population simulations at the species exposure level are currently underway for the North Atlantic right whale, the southern right whale, and the western gray whale. However, participants also expressed the need for a paradigm shift in management processes to move the focus from projects to the resources or species intended for preservation. Fortunately, several governments are discussing concepts such as marine spatial planning and marine zoning that would facilitate better CIAs. Meanwhile, participants of the workshop noted that cumulative impacts are a threat to marine life and that the reduction of ocean noise is an achievable goal that would help marine life cope with less tractable threats such as climate change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The material presented here regarding cumulative impact assessment primarily represents the combined effort of all the participants of the 2009 workshop sponsored by Okeanos - Stiftung für das Meer (Foundation for the Sea). The author here acts as a reporter only and the Report of the Workshop On Assessing The Cumulative Impacts Of Underwater Noise With Other Anthropogenic Stressors On Marine Mammals: From Ideas To Action, should be considered as the definitive source.

SOURCES

Halpern, B.S., Kappel, C.V., Selkoe, K.A., Micheli, F., Ebert, C.M., Kontgis, C., Crain, C.M., Martone, R.G., Shearer, C. & Teck, S.J. 2009. Mapping cumulative human impacts to California Current marine ecosystems. Conservation Letters 2:138–148

Wright, A.J. (ed) 2009. Report of the Workshop on Assessing the Cumulative Impacts of Underwater Noise with Other Anthropogenic Stressors on Marine Mammals: From Ideas to Action. Monterey, California, USA, 26th-29th August, 2009. Okeanos - Foundation for the Sea, Auf der Marienhöhe 15, D-64297 Darmstadt. 67+iv p. Available from http://www.sound-in-the-sea.org/download/CIA2009_en.pdf.