Tara Rodriquez – tara@ling.ucsd.edu

Amalia Arvaniti – aarvaniti@ucsd.edu

University of California, San Diego

9500 Gilman Dr.

La Jolla, CA 92093-0108

Popular version of paper 5aSCa6

Presented Friday morning, November 4, 2011

162nd ASA Meeting, San Diego, Calif.

As anyone who has listened to a language they do not speak can testify, speech is an undivided stream of sounds that blend into each other. It is only our knowledge of a given language that makes us distinguish individual words and sounds.

The question that arises from this observation is one to which researchers have no satisfactory answer yet: how, starting in infancy, do humans learn to pick out words and sounds in the speech they hear around them?

One popular view connects language acquisition to prosody, the modulation of speech in terms of rhythm and pitch, and especially to a view of rhythm according to which languages are divided into rhythm classes: stress-timing, exemplified by English, and syllable-timing, exemplified by Spanish. According to this view, the speech characteristics of each class allow infants to figure out which class their language belongs to, leading them to focus their attention on their language’s rhythm unit and from there to the segmentation of speech into words. For example, in English attention is focused on stresses, like the win part of win.dow; since stresses are largely word-initial in English, this strategy works well to identify the beginnings of words.

The properties that differentiate rhythm classes are unclear, however. For some, the difference lies in the regular occurrence of each class’s unit: stresses are said to occur at regular intervals in stress-timed languages, while syllables are said to be of similar duration in syllable-timed languages. Others attribute rhythm class differences to syllable structure. Languages like English have complex and varied syllables: both awe, pronounced as one long vowel, and strengths, which includes several consonants before and after the vowel, are one syllable long. In syllable-timed languages like Spanish, on the other hand, the majority of syllables consist of one consonant followed by one vowel; e.g. felicidad “happiness.” Although acoustic evidence has failed to corroborate either view, perception research offers some support for rhythm classes: in experiments in which the stimuli are manipulated to mask language identity listeners can discriminate languages belonging to different rhythm classes but not languages from the same class. There are, however, exceptions: e.g. English and Polish, though both classified as stress-timed, are discriminated from each other.

These exceptions suggest that reasons other than rhythm class may be behind successful discrimination. This is a possibility because discrimination experiments require listeners to simply decide whether the stimuli they heard are the same or different, and researchers can only surmise that the responses are due to the feature they are manipulating. Such features, however, co-exist with others which may contribute or even be responsible for the results. Such a confound may affect the rhythm discrimination experiments, since many of the stress-timed languages tested, such as English, are spoken at a slower speaking rate (or tempo) – measured in syllables per second – than the syllable-timed languages they were compared to, such as Catalan.

The possibility that differences in tempo are the underlying cause of successful discrimination was investigated in a series of AAX (or oddball) experiments that also examined the role of pitch modulation (or intonation) in discrimination. In each trial, listeners heard two English sentences followed by a sentence from another language and had to respond if the third sentence came from the same language as the first two.

In order to disguise the identity of the languages, speech synthesis was used to convert the sentences into sasasa sequences by replacing all consonants with [s] and all vowels with [a]; e.g. cat becomes sas, and felicidad becomes sasasasas.

Audio file 2. The word adventure, taken from one of the experimental sentences, followed (i) by its sasasa version with original pitch (adapted to the range of the speaker whose voice was used for synthesis) and (ii) with “flat” pitch

In one experimental condition, the sasasa stimuli kept the tempo of the original sentences, while in the other the tempo was altered so that all stimuli had the same tempo (the average of the original sentences in that experiment). Within each of these two conditions, the stimuli were presented to listeners either with their original pitch or with “flat” slightly declining pitch. It was hypothesized that having both tempo and pitch information would aid discrimination, that having neither would make discrimination impossible, and that stimuli differing only in pitch or tempo would show intermediate results.

Five experiments were designed using this set up, comparing English to Polish, Danish, Spanish, Greek and Korean. Polish and Danish are considered stress-timed but are spoken at different rates: Polish is faster than English (6.5 syllables/second vs. 4.8 for English) while Danish tempo is similar to English (5.1 syllables/second). Spanish, Greek and Korean are considered syllable-timed, but differ in tempo: at 4.8 syllables/second Korean is spoken as slowly as English, while Greek is much faster (6.8 syllables/second) and Spanish intermediate (6.1 syllables/second). If rhythm class is the origin of successful language discrimination in earlier experiments, then Polish and Danish should not be discriminated from English (since they belong to the same rhythm class), but Greek, Spanish and Korean should. If tempo is the reason behind discrimination, then Polish and Greek, which are spoken much faster than English, should be discriminated from it, but Danish and Korean, whose tempo is similar to English, should not.

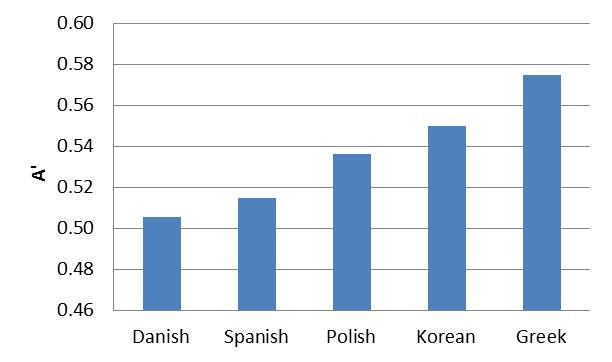

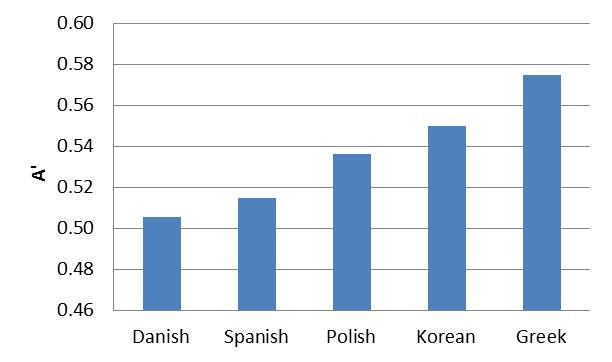

The results from 24 participants in each experiment (120 total) showed that rhythm class played little role in discrimination: Danish and Spanish were not discriminated from English although the former is stress-timed and the latter syllable-timed (see Figure 1). Tempo, on the other hand, did affect discrimination: when tempo information was present, discrimination was possible, but when tempo differences disappeared, listeners were simply guessing (compare the first two columns of Figure 2 with the last two columns).

Figure 1: Discrimination by language; a score of 0.50 means that listeners were guessing.

Figure 2: Discrimination by experimental condition; a score of 0.50 means that listeners were guessing.

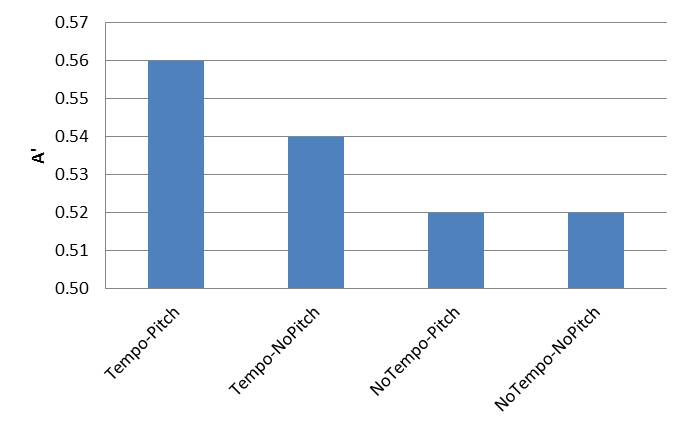

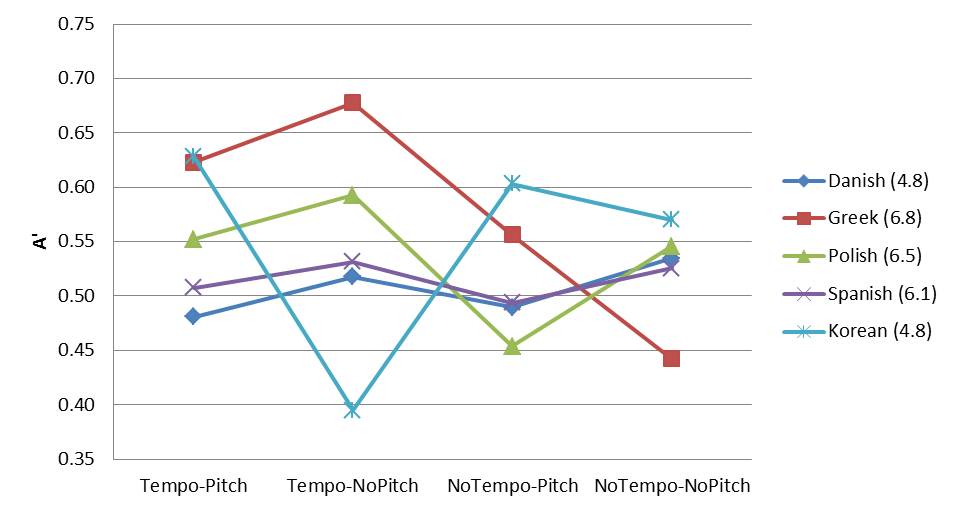

When results were broken down by language, the role of tempo and pitch (but not of rhythm class) was confirmed (see Figure 3). Danish was not distinguished from English, but stress-timed Polish and syllable-timed Greek – both fast-spoken languages – were equally well discriminated from English. The role of pitch was secondary: it did not help when intonation was of similar structure to that of English (as in the case of Danish) but it did help when intonation differences were large and tempo differences small. This was the case with Korean: Korean was confused with English when pitch was “flat”, but was successfully discriminated from it when intonation information was present (Tempo-Pitch and NoTempo-Pitch in Figure 3). This can only be attributed to the rapid rise-fall-rise pitch pattern that Korean exhibits on most words in a sentence, a pattern that is very different from the slower pitch modulations found in English. In the case of Greek and Polish, on the other hand, the presence of intonation impeded rather than facilitated discrimination. This was most likely due to the fact that their pitch movements, which are comparable to those of English, interacted with tempo attenuating the tempo effect.

Figure 3: Discrimination by language and experimental condition; a score of 0.50 means that listeners were guessing

Overall these results suggest that discrimination between languages is not connected to rhythm class. Rather, previous experiments may have interpreted as an effect of rhythm class the fact that tempo is often (though not always) slower in languages classified as stress-timed than in those classified as syllable-timed. The results also show that features like rhythm, pitch and tempo interact with one another in ways that can affect the perceptual impression languages give. In turn, these results question the idea that infants exploit rhythm class distinctions to attain language acquisition.