Melissa A. Redford – redford@uoregon.edu

Department of Linguistics

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon 97403-1290

Hema Sirsa – hsirsa@uoregon.edu

Department of Linguistics

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon 97403-1290

Irina A. Shport – ishport@uoregon.edu

Department of Linguistics

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon 97403-1290

Popular version of paper 5aSCa

Presented Friday morning, November 4, 2011

162nd ASA Meeting, San Diego, Calif.

Lay Language Version

The temporal patterning of vowels in a language gives rise to the percept of language rhythm. Different languages have different rhythm patterns. Consider, for example, the rhythm of Spanish and Korean compared to that of English and Russian. Whereas the vowels of Spanish and Korean are perceived as being regularly spaced and equal in duration, the vowels of English and Russian are less regularly spaced and longer vowels alternate with shorter ones. Previous work on the acquisition of language rhythm by preschool children suggests that children master the rhythm of languages like Spanish sooner than the rhythm of languages like English (Grabe et al., 1999; Bunta & Ingram, 2007; Payne et al., in press). Our work with school-age children indicates that adult-like rhythm in English may not be acquired until 6 or 7 years of age (1st or 2nd grade). Specifically, we measured sequential vowel durations in experimentally controlled sentences and found that the rhythm of 5-year-old children’s speech was distinct from the rhythm of 8-year-old children’s speech. A year later, the same children produced the same sentences and we completed the same measurements. We found that rhythm had changed significantly in the younger children’s speech and was more similar to the rhythm of older children’s speech, which had not changed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Developmental change in speech rhythm for a younger and older group of school age children in our cross-sectional and longitudinal study on the acquisition of English rhythm.

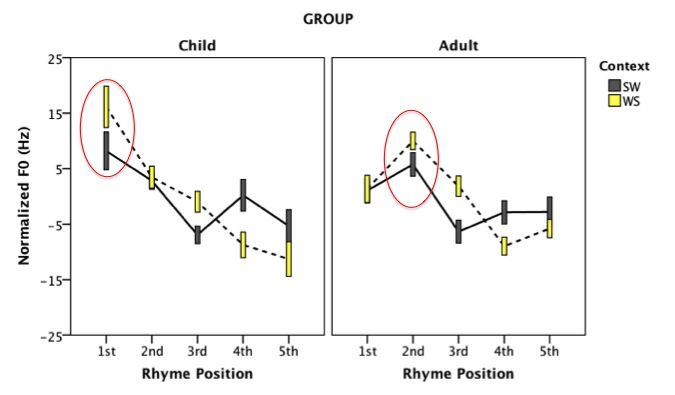

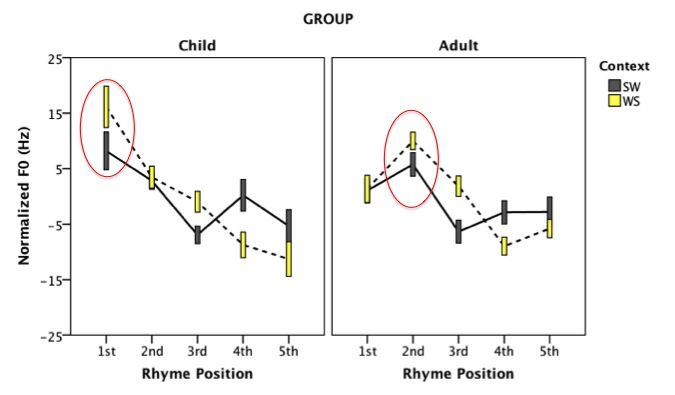

Mastery of the temporal patterning of vowels in English requires mastery of the various prosodic units that give rise to different vowel durations. These units include (1) word-internal feet, which describe the word-internal patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables (e.g., “baNAna” versus “BARbecue”), (2) phonological phrases, which describe the rhythmic grouping of adjacent words (e.g., “the DOG” versus “THE” “DOG”), and (3) intonational phrases, which describe the grouping of word strings (e.g., “the girl walked the DOG, and the boy…” versus “the girl walked the dog to SCHOOL”). Our work suggests that the surprisingly slow acquisition of English rhythm may be due to the extended acquisition of phrase-level units rather than to immature production of word-level patterns. For example, we used a counting task in another study to induce maximally rhythmic speech (e.g., 1 banana, 2 banana, 3 banana …) and found that the acoustic correlates of word-internal stressed and unstressed syllables were the same in 6-year-old and adult productions of two and three syllable words. However, we also found that children and adults differed in their placement of phrase-level accents, which are conveyed using pitch (F0): children consistently produced the highest F0 on the initial syllable of the phrase, whereas adults consistently produced the highest F0 on the earliest stressed syllable in the phrase (Figure 2). Thus, only adults aligned phrase-level accents with word-level stress. The alignment of an accent with a stressed syllable results in cumulative prominence, which defines the focal point of a phrase-level prosodic unit.

Figure 2. Accent placement (highest F0) in child and adult productions of phrases produced during a counting task. The SW context refers to phrases with the word barbeque (e.g., “fourteen barbeque”). The WS context refers to phrases with the word banana (e.g., “fourteen banana”).

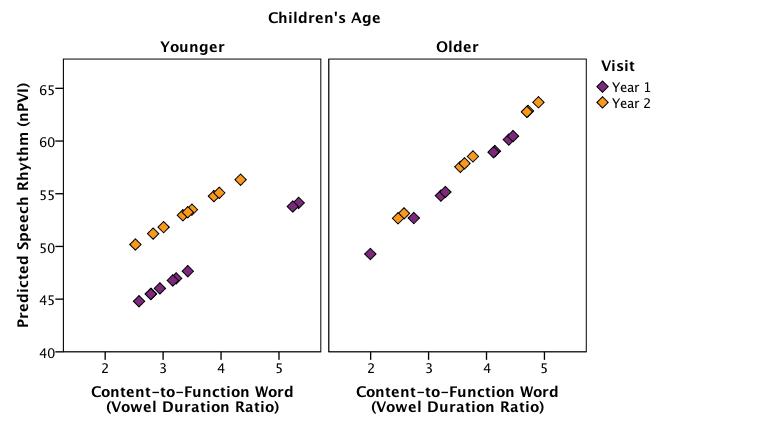

The acquisition of phrase-level prosodic units may depend as much on the ability to reduce (de-emphasize and shorten) vowels in supporting words as on the ability to define the focal point of the unit via cumulative prominence. And there is some evidence to suggest that children are less able to reduce vowels than adults (Redford & Gildersleeve-Neumann, 2009). The ability to reduce the vowels of supporting words in a phrase may also be crucial to the acquisition of adult-like language rhythm. Consistent with this claim, we found in our cross-sectional and longitudinal data that the best predictor of adult-like rhythm was the ability to reduce the vowel in a function word (“the”) relative to that of an adjacent content word (e.g., “dog”) in multiword sentences (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The ratio of vowel durations in adjacent content and function words (e.g., “the dog”) was the best predictor of speech rhythm in our cross-sectional and longitudinal study on the acquisition of English rhythm.

Studying the acquisition of language rhythm allows us to better understand its developmental progression. This understanding can then be applied to designing interventions with children or adults who have disorders that affect language rhythm. The remediation of language rhythm is important since unusual rhythm patterns contribute significantly to the perception of communication disorder. So far, our results suggest that speech and language pathologists could adapt methods from traditional articulation therapy and use some fluency shaping techniques to remediate atypical rhythm. That is, intervention may be most successful if the focus is on remediating rhythm first in smaller prosodic units, then in increasingly larger ones, which appears to be the way in which English rhythm is typically acquired. Once word-level patterns have been appropriately integrated into phrase-level units, therapy could shift to focus on grammatically appropriate phrasing of longer and longer utterances.

This research was supported by Award Number R01HD061458 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NICHD or of the National Institutes of Health.

References

Bunta, F. & Ingram, D. (2007). The acquisition of speech rhythm by bilingual Spanish- and English-speaking four-and five-year-old children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 50, 999-1014.

Grabe, E., Gut, U., Post, B. & Watson, I. (1999). The acquisition of rhythm in English, French, and German. In I. Barriere, G. Morgan, S. Chiat & B. Woll (eds.), Current research in language and communication: Proceedings of the child language seminar (pp.157-163). London: City University.

Payne, E., Post, B., Prieto, P., del Mar Vanrell, M., & Astruc, L. (in press). Measuring child rhythm. Language and Speech.

Redford, M.A., & Gildersleeve-Neumann, C.E. (2009). The development of distinct speaking styles in preschool children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 1434-1448.