Braxton Boren – bbb259@nyu.edu

New York University

35 W. 4th St.

New York, NY 10012

Malcolm Longair – msl1000@cam.ac.uk

University of Cambridge

JJ Thomson Avenue,

Cambridge CB3 0HE.

Popular version of paper 1aAA6

Presented Monday morning, October 31, 2011

162nd ASA Meeting, San Diego, Calif.

Introduction

Renaissance Venice was the site of incredible artistic and musical innovations. Architectural masterpieces such as the Basilica of San Marco and Palladio’s Redentore were home to the musical innovations of increasingly complex multi-part (or polyphonic) music as well as the split-choir coro spezzato, the first use of a spatial ‘stereo’ effect in Western music.

But historians have raised many questions about this period: how could complex polyphonic music be heard in these huge, reverberant churches? How pronounced was the spatial effect of the coro spezzato? To answer these questions, we will use Acoustic Archeology – a scientific technique that allows us to listen to Venice as it sounded 400 years ago.

Redentore

Many of the innovative musical works being composed at this time in Venice would have been performed at masses in San Marco and other major churches such as the massive Redentore (fig. 1), designed by Andrea Palladio. However, modern acoustic measurements show the Redentore to be highly unsuitable for fast-tempo, polyphonic music. The church’s reverberation time – the time it takes for a sound to decay to inaudibility – is greater than 7 seconds. This reverberation blurs fast music, reducing its clarity and intelligibility.

Fig. 1. Interior of the Redentore, high altar

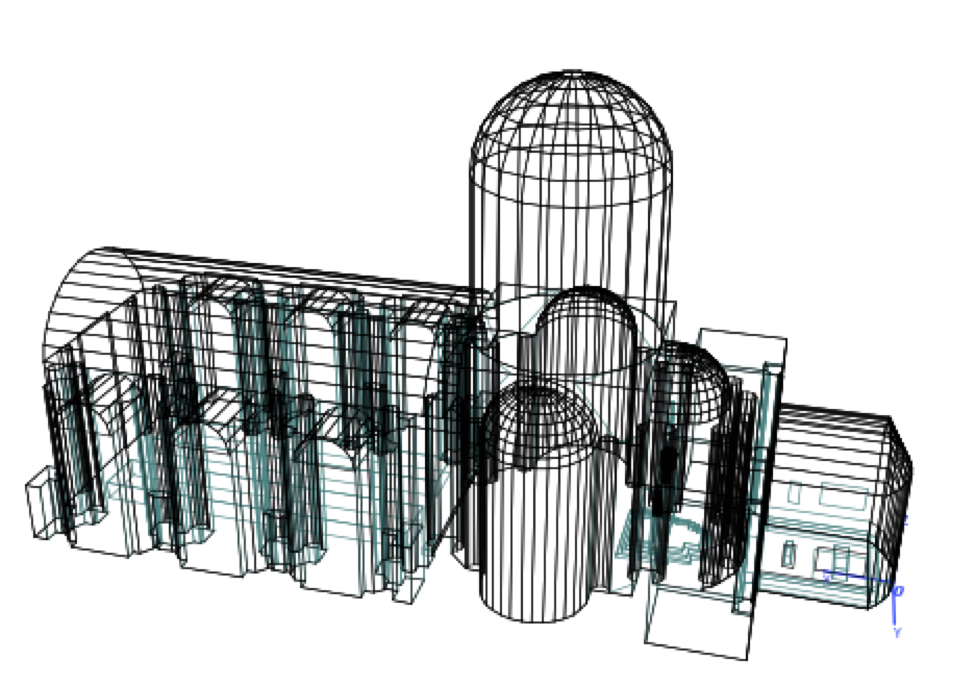

The empty Redentore in the Renaissance would likely have sounded very much like the church today. It was only used for a high mass in the presence of the Doge, the nobility, and the broader populace once per year, on the annual Festival of the Redentore. During the rest of the year, the monks who lived there would have sung simpler monophonic chants. On the day of the festival, however, the church would have been completely filled with people, tapestries, and temporary wooden seating in the chancel. By consulting with architectural historians, we were able to estimate the absorptive properties of these materials and audience members. To compare the present and past church’s acoustics, we constructed a computer model of the present-day Redentore (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Computer acoustic model of Redentore

This model’s acoustic simulations matched the extensive measurements for reverberation time that had been taken in the present-day undecorated church. Then, we altered the computer model by introducing the audience, tapestries, and seating. This “festal church” model predicted that the people and decorations would introduce significant absorption into the church. In fact, the reverberation time would be cut in half! This suggests that full, decorated churches would have had much greater clarity but lower overall loudness when listening to complex polyphony.

Using our acoustic model, we can predict the time and intensity of nearly all the sound reflections in the Redentore. If we then record a choir singing in an anechoic chamber, which has no echoes, we can combine this anechoic recording with the reflections from the model to hear what the choir would sound like when singing in the virtual space. This process, called auralization, is useful to subjectively evaluate acoustics of the church at different points in history. As we combine a single anechoic recording with the different models, we can hear the change in overall reverberation. Figure 3 allows instant comparisons between the anechoic, “empty church,” and “festal church” versions of Monteverdi’s Cantate Domino.

Fig. 3. Audio simulations of the empty and festal Redentore using anechoic recording

San Marco

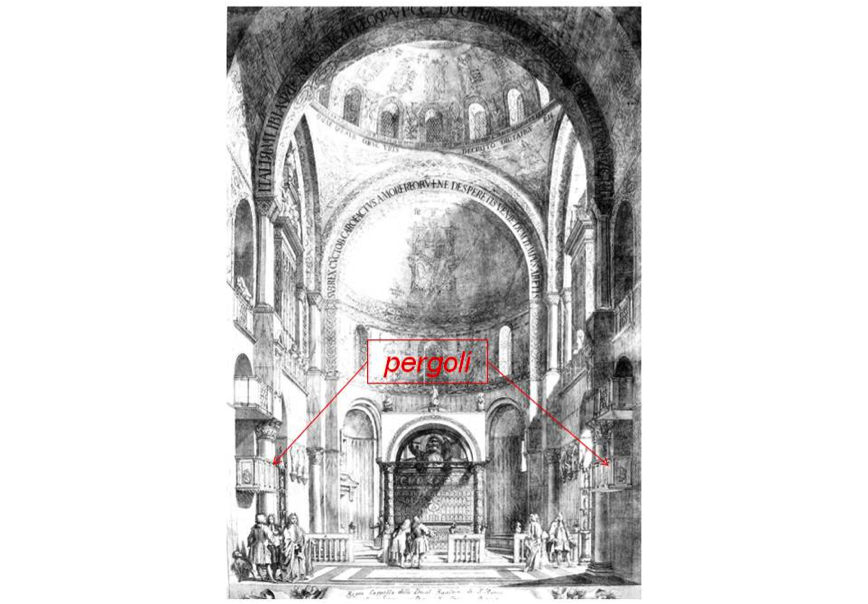

There is some uncertainty about where the split-choir music was performed in San Marco. Though at one point the entire choir certainly performed in a single location, there are other recorded remarks about the split choirs being placed far apart. One theory holds that the architect Jacopo Sansovino placed raised galleries (called pergoli) on both sides of the chancel, in the front of the church, to enhance the stereo effect for the Doge’s throne in the center. It stands to reason that the architects and composers working in San Marco had more incentive to please the Doge (their employer and ruler of the Venetian Republic) than the rest of their audience. Figure 4 shows Sansovino’s pergoli in an 18th century depiction of San Marco’s chancel.

Fig. 4. Sansovino’s pergoli in Visentini’s View of the Chancel of San Marco, 18th century

Modern acoustic measurements have shown that sound sources in the pergoli have an excellent blend of resonance and clarity at the position corresponding to the Doge’s throne. Even in the empty church, the Doge’s position has a reverberation time of 4 seconds, while listeners in the nave experience a reverberation time of nearly 7 seconds. To analyze the Doge’s position more closely, we constructed an acoustic model of San Marco (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Computer model of San Marco – chancel is on the far side of the columned screen

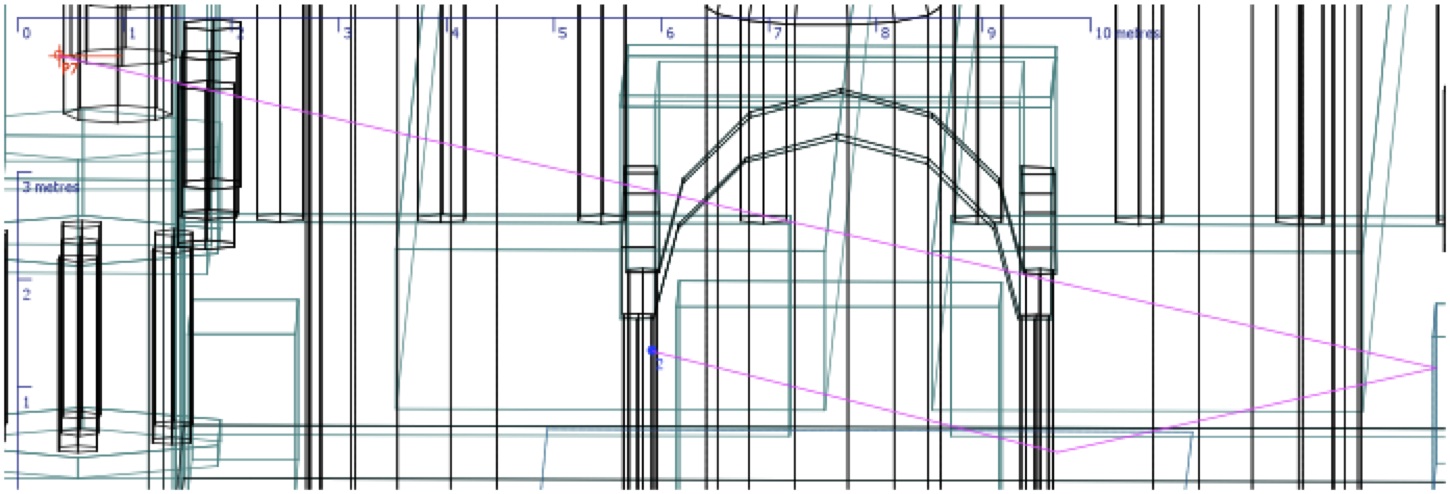

Much of the auditory information needed to understand what we hear is contained within the first several milliseconds of a sound reaching our ears. Musical clarity is determined by the ratio of this early sound reaching a position to the later reflections that create reverberation. Since a columned screen separates the chancel from the rest of San Marco, the early sound is much louder there. However, a geometrical analysis showed that Sansovino’s extended pergoli help give a direct line-of-sight from the choir’s position to the Doge’s throne. The previous galleries before Sansovino would not have provided this direct line, and so the first sound to reach the Doge would have bounced off a wall and the floor (fig. 6). This would have delayed the early sound and made it much quieter, reducing the overall clarity of the performance.

Fig. 6. Earliest sound path to Doge’s position when choir gallery does not provide a direct line-of-sight

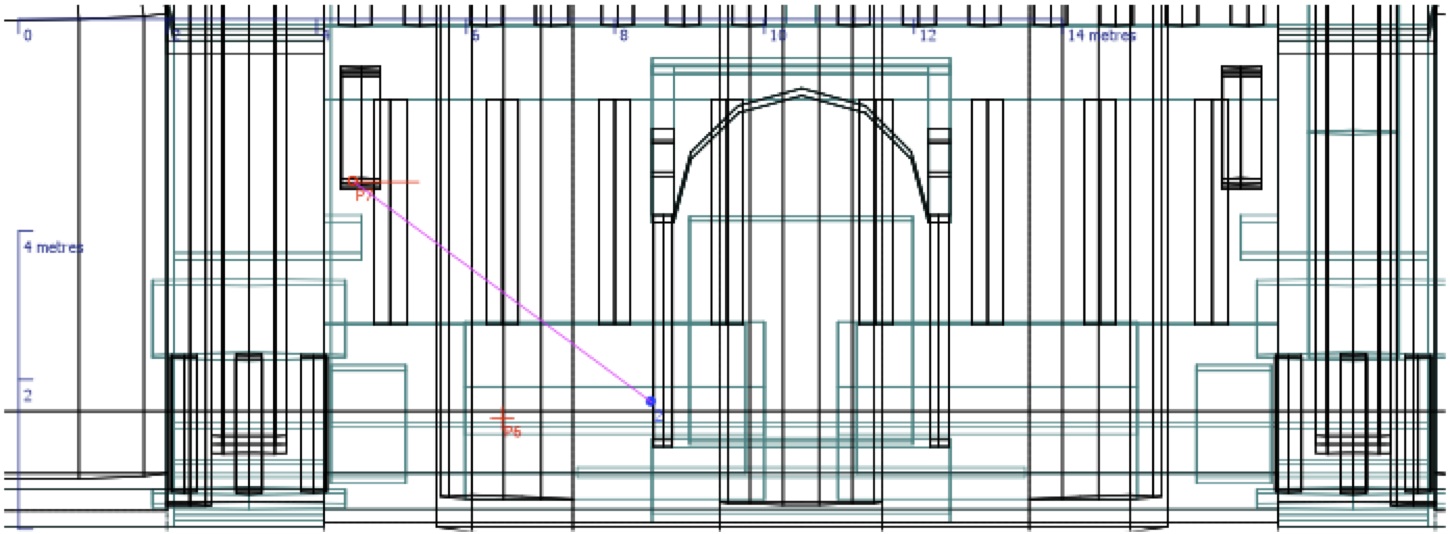

But with the virtual source at the edge of Sansovino’s pergolo, the direct sound (fig. 7) arrives 45 milliseconds earlier and is 14 decibels louder. This drastically improves the clarity at the Doge’s position.

Fig. 7. Direct line-of-sight formed with source at the edge of Sansovino’s pergolo

Like the Redentore, San Marco was filled with people and decorations for festive occasions and holidays. Using paintings of the festal chancel, the computer model was able to simulate the effect of this change, again increasing clarity but reducing overall loudness. The model predicts that the reverberation time at the Doge’s position in the festal church would have been between 1.5 and 2 seconds, which is the desired range for modern concert halls today! In addition, the direct line-of-sight ensures that the choir’s overall volume was still sufficiently loud in the chancel, even if it may have sounded quieter for the audience in the rest of the church. Figure 8 allows a direct audio comparison of the empty and festal church when the choir is in Sansovino’s pergolo, listening from the Doge’s throne.

Fig. 8. Audio simulations of the empty and festal San Marco chancel using anechoic recording

Conclusions

Using modern acoustic simulation technology, past versions of two major Renaissance churches have been modeled and analyzed. Both numerical analysis and auralization allow a different way of evaluating historical questions. Careful research into the material components of the festival suggests that on the single day of the year when a high mass was performed in the Redentore, the added absorption would have increased the musical clarity of choral performances. In San Marco, a geometrical analysis shows that Sansovino’s extended galleries were essential to the favorable musical acoustics at the Doge’s throne. This evidence supports the conclusion that Sansovino constructed the pergoli for the purpose of enhancing the split-choirmusic for his employer, the Doge. Even in the Renaissance, it took money and power to get a really top-notch sound system.