Ed King – etking@stanford.edu

Meghan Sumner – sumner@stanford.edu

Department of Linguistics

Margaret Jacks Hall, Bldg 460

Stanford University

Stanford, CA 94305-2150

Popular version of paper 3aSCb19

Presented Wednesday morning, November 2, 2011

162nd ASA Meeting, San Diego, Calif.

Speech is full of variation. A particular word may be uttered differently each time it is produced depending on speaking rate, listening condition (such as ambient noise), and mood. Adding accents to the mix increases the variation considerably. Given the massive variation in natural speech, how listeners understand spoken words is a central issue for linguistic theory.

Consider the word butter. The most common way for a General American (GA) speaker to say this word is with a medial tap, sounding like budd-er. But listeners change their speaking style depending on social context. I might produce this word with a [t], sounding like butt-er in a formal ceremony speech, or when helping my daughter spell the word.

Speakers adjust speech in accord with the social context.

Variation is also manifested across phonological systems of different dialects. A speaker of the New York City dialect may produce a schwa (like the final sound in sofa) in place of –er in the word butter. And, while a formal situation might prompt a medial [t], it would not prompt a final schwa. A speaker of British English Received Pronunciation (RP) will have yet another production, a schwa with an intervocalic [t], even in casual speech [1-3].

As listeners, we need to understand words produced differently as an instance of one word rather than another, similar word. And, if we think of how much variation exists in speech, we might be amazed at ourselves – we typically accomplish this daunting task on a daily basis without much issue at all. We meet different people, listen to TV and radio shows with speakers of different accents, and generally understand spoken language despite this massive variation.

One question we are interested in is how we as listeners use what we know about language patterns (or what we believe we know) to help us navigate this highly variable speech stream. Answering this question will inform us about the types of representation used by listeners during speech perception, and help us understand how past experience with an accent or speech pattern helps people understand spoken words.

One way listeners adjust to variable speech is via perceptual learning. Perceptual learning is a learned shift in behavior that is prompted by exposure to a sound that is ambiguous between two other sounds [4]. For example, researchers take a manipulated speech sound that sounds like ‘s’ half the time and ‘sh’ half the time to naïve listeners, and embed that sound in words. These words are either ‘s’-frames (e.g., lace, where lashe is not a word) or ‘sh’-frames (e.g., blush, where bluss is not a word). When this ambiguous sound is presented in these frames, listeners who heard lace with the ambiguous sound shift perception and categorize that sound as ‘s’ more than speakers who heard the sound embedded in bluss. This shift has been claimed to be central to a listener’s ability to adjust to the variety of accents they hear.

Variation across accents, though, is more nuanced than slight differences at the boundary between sounds. And, as shown by Hay and colleagues [5], listeners perceive vowels differently depending on visual cues that index a particular accent (e.g., seeing something that reminds a speaker of a particular accent influences how they categorize speech sounds).

We explore whether continued exposure to an accent makes it easier to understand sounds that are different from one’s own dialect – even without hearing those sounds. Expanding on shifts like those previously studied, we want to show how hearing speech with phonetic cues that make someone sound British help listeners understand sounds that might typically be costly during speech perception. The first step is to show that the benefit to a listener based on expectations increases with exposure to cues that signal a particular accent.

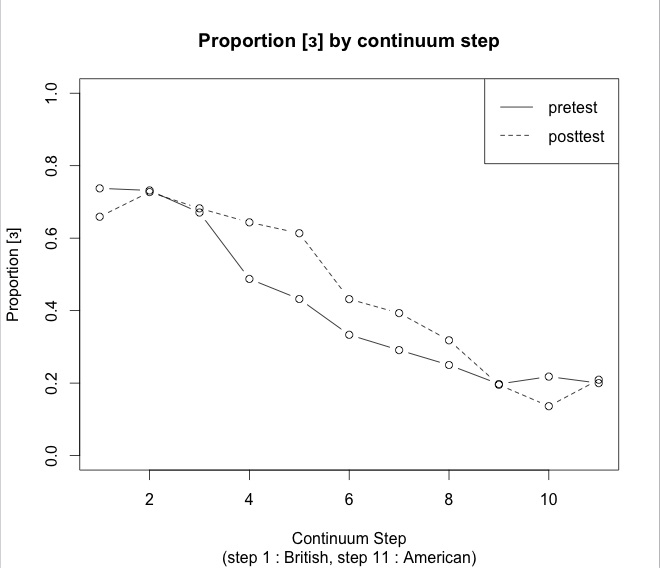

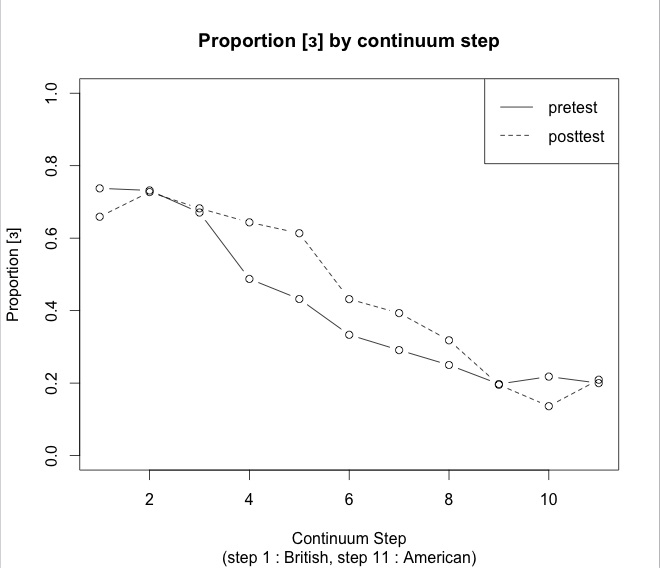

In our study, listeners first categorized a continuum produced by an RP speaker. We then presented listeners with an exposure phase. In this exposure phase, listeners were presented with words (e.g., ball) and pseudowords (e.g., gruss) and were asked to make a lexical decision for each item (e.g., Is this a word or a pseudoword?). Critically, no words contained the vowel of interest. Listeners were simply exposed to the accent. Finally, listeners categorized sounds along the SNER continuum again (post-test). We measured the percent of “uh” responses (where “uh” is the sound at the end of words like slender in RP) made in the post-test compared to the pre-test. Figure 1 shows the proportion of “uh” responses to each stimulus for the pre-test and the post-test. A shift beyond the pre-test is not predicted via perceptual learning, since listeners were not presented with the sound in question. Our results show that listeners clearly heard more RP vowels than AE vowels after exposure to the RP accent (without exposure to the critical sounds).

Figure 1. Proportion “uh” responses (y-axis) averaged across subjects for each continuum step (x-axis). Pre-test means are represented with solid line, and post-test means are represented with dashed line.

There is no a priori reason why continued exposure to an accent should make a listener hear more RP vowels unless (1)listeners apply a pattern learned over time to the stimuli cued by the accent or (2)exposure to an accent increasingly heightens activations of forms in the accent. This shift raises questions about the nature of familiarity with an accent, issues with non-typical speakers of a stereotyped accent, and whether stereotype-congruent patterns are facilitated more than stereotype-incongruent patterns. For example, as a GA speaker, I believe that British speakers produce –uh at the end of words like slender. Do I understand speakers that follow this pattern more than those that don’t, even if the non-stereotyped pattern (e.g., a British speaker who has an –er similar to GA) is found in my own dialect? In other words, do the cues that tell me a speaker is British (to my ears) make it easier to understand sounds that I do not have in my dialect, relative to those sounds that I do have in my dialect but that do not match my stereotype of that speaker group? We believe the answer is yes.

The important point here is that continued exposure to an accent alters a listener's perception of the sounds within that accent, and results in shifts greater than those based on expectations alone. This supports the notion of accent clouds stored in memory, and has the potential to shed light on the composition of these clouds. We believe that this is a rich area to explore to help us begin to understand the links between actual experience, stereotyped experience, and speech perception.

[1] Fischer, J. L. (1958). Social Influences in the choice of a linguistic variant. Word, 14, 47-56.

[2] Labov, W. (2006). The social stratification of English in New York City. Washington D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics.

[3] Trudgill, P. (1974). The social differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

[4] Norris, D., McQueen, J.M., & Cutler, A. (2000). Merging information in speech recognition: Feedback is never necessary. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 299-370.

[5] Hay, J., & Drager, K. (2010). Stuffed toys and speech perception. Linguistics, 48, 865-892.