Performances of George Antheil's 1924 Ballet mécanique

Paul D. Lehrman, lehrman@pan.com

Department of Music

Tufts University

Medford, MA 02155 USA

A presentation on videotape, co-produced by

Howard Woolf, howard.woolf@tufts.edu,

and the Tufts University Video Laboratory

Popular version of paper 3aAA4

Presented Wednesday morning, December 6, 2000

ASA/NOISE-CON 2000 Meeting, Newport Beach, CA

|

|

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

of the Performing Arts

|

George Antheil's Ballet mécanique may be the most famous unknown piece of the 20th century. Famous, because at its Paris premiere it caused a riot that eclipsed even the melee that welcomed Stravinsky's Rite of Spring , thus catapulting Antheil, at the age of 25, to the pinnacle of Parisian artistic society. Unknown, because until 1999, the Ballet mécanique , in the way the composer had originally conceived it, had never been heard by anyone. But thanks to late-20th century technologies include desktop computers, the Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI), and MIDI-compatible player pianos like Yamaha's Disklaviers, it is now possible for Antheil's youthful dream to be realized.

Antheil was a young American composer and pianist who arrived in Paris in 1923, and immediately found himself part of a circle inhabited by the greats of the European and expatriate avant-garde arts and letters: James Joyce, Stravinsky, Ezra Pound, Picasso, Fernand Léger, Gertrude Stein, and many others. His own music reflected the machine-age aesthetic of the times, and was designed largely to shock and open audiences' ears, incorporating such revolutionary elements as atonalism, jazz, ragtime, and noise. His crowning glory was to be the Ballet mécanique, which he scored for two grand pianos, three xylophones, four bass drums, a tam-tam, a siren, three airplane propellors, several electric bells, and 16 synchronized player pianos, playing four separate parts.

While the player piano had been around for some 30 years, and other composers like Stravinsky, Ravel, and Hindemith had written or arranged pieces for the popular mechanical instruments, Antheil's youthful magnum opus was the first concert work to call for multiple player pianos. He knew he was breaking new ground when he started writing the piece in 1924, but he didn't know how far into the future he was reaching. The technology to play the piece, or so he thought, already existed: Pleyel, a Paris piano maker with whom Antheil worked closely, had designed and even patented a system for synchronizing multiple player pianos, using electric motors and a sophisticated speed-adjusting system that bears a striking resemblance to the timecode technology used today to synchronize electronic sound and images. Unfortunately, it appears that Pleyel never actually built a working system.

Antheil and his friends made up all sorts of excuses as to why the premiere of the piece was being delayed (Pleyel was having trouble making the paper rolls, there wasn't enough electricity in any hall in Paris to power that many player pianos, etc.), but the truth was that there were simply no instruments in existence that could play the piece. When he finally realized this was the case, Antheil re-wrote the piece for a single player piano and multiple human-played pianos, and that version was heard, to great acclaim andequally great condemnation, on a number of occasions in Paris, the most famous being a concert at the Théâtre Champs-Elysées which caused Aaron Copland to proclaim that Antheil "had Paris by the ear."

|

|

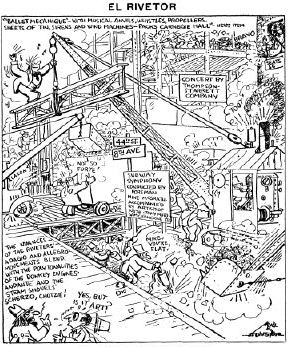

Cartoon from the New York World,

following the infamous Carnegie Hall concert.

Courtesy of the estate of George Antheil |

In 1927, the piece came to New York's Carnegie Hall, but there it met with only derision — an inexperienced promoter ludicrously over-hyped the event, much-anticipated riots never materialized, and technical failures abounded. Antheil went back to Paris with his tail between his legs, his reputation as a serious composer in ruins. This version of the piece was not played again until 1989 when conductor Maurice Peress revived it for a performance (at Carnegie Hall) and a recording.

Antheil returned to America for good in the early 1930s, and after some time managed to regain some of his reputation as a composer, and also made a decent living composing film and television scores. In 1952, with the encouragement of friends, Antheil re-wrote the Ballet mécanique, adding more percussion, and dispensing with the player pianos altogether. It is this version that most people who are familiar with the piece today have heard, as it is performed frequently and has been recorded several times. Antheil died in 1959, at the age of 58.

In the early 1990s, Antheil's catalogue passed into the hands of G. Schirmer,

the New York music publishing house. In 1996, the Ensemble Moderne in Germany

arranged the first performance of the 1924 version of the piece, using two custom-modified

MIDI-controlled player pianos to perform the four parts, and creating MIDI sequence

files from Antheil's original piano rolls. But William Holab, then director

of publications at Schirmer, wanted to create a version of the piece that any

group could play on easily-obtainable instruments, and so he commissioned the

current author to create a four-part MIDI sequence from Antheil's original score

(which was far more accurate than the rolls), which could then be easily distributed

on a CD-ROM as a Standard MIDI File and played through common MIDI sequencing

software. At the same time, he contacted Michael Bates, director of academic

and institutional relations for Yamaha pianos, and asked him if Yamaha would

support one or more initial performances of the piece by lending Disklaviers

to potential performing groups. Bates, seeing both the "coolness"

factor and the public relations potential in participating in such an enterprise,

agreed.

The piece is massive: there are 1240 measures, with over 600 time signature

changes, and complex, blazing-fast rhythmic figures and huge block chords throughout.The

music was entered from the printed score prepared by Schirmer, into a Macintosh

MIDI sequencing program called Vision, made by Opcode Systems. The process took

about six solid weeks of work.

|

|

example of sequenced player-piano

part

|

In order to make the piece as easy as possible for musical groups to perform, this author also agreed to supply Schirmer with digital samples of the airplane propellers, the bells, and the siren, in several common sampler formats (Kurzweil, Akai, SampleCell), which could also be distributed on CD-ROM. The airplane samples were recorded by Tim Tully at a private airfield in San Carlos, California; this author recorded the siren at the Arlington, Massachusetts, fire station; and the bells were recorded in my home studio. The sequences containing the player-piano parts also contain tracks for all of the sound-effects parts, and so performing groups have a choice: they can use the sequenced effects tracks and have them play automatically, or they can use live MIDI keyboard players to play the samples.

There are other alternatives as well. In two performances, a real siren has

been used. Engineer Coleman Rogers and this author designed and built a contraption

comprising seven different-sized electric bells and a series of relays, controlled

by a MIDI-to-relay converter made by MIDI Solutions of Vancouver, Canada. This

"MIDI Bell Box" is designed to be hung above the stage, and it too can be played

automatically from the computer sequencer, or by a live musician playing a MIDI

keyboard.

|

|

MIDI Bell Box

|

The world premiere of the 1924 version of the Ballet mécanique in its original instrumentation took place on November 18, 1999, at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, where I was teaching at the time. It was conducted by Jeffrey Fischer of the UMass faculty, and the piano soloists were Juanita Tsu, also of UMass, and John McDonald of Tufts University. The percussion parts were handled by the student percussion ensemble, who dedicated 10 weeks of rehearsal to the piece and turned in an outstanding performance.

As they promised, Yamaha supplied 16 Disklaviers for the performance,

and took care of the expense of moving and tuning them. The concert, which also

included works for player pianos, percussion, and/or electronics by John Cage

and Lou Harrison, Amadeo Roldán, Conlon Nancarrow, Richard Grayson, and

Felix Mendelssohn (arranged by this author), was simul-Webcast on wgbh.org,

the site belonging to Boston's major National Public Radio affiliate. The sold-out

crowd gave the students a standing ovation, and reviewers from Boston to San

Francisco were generous in their praise.

|

|

World Premiere of the revived 1924

Ballet mécanique, November 18, 1999 in Lowell, Massachusetts

|

Antheil returned to Carnegie Hall on April 2, 2000, when the American Composers

Orchestra performed the piece under the baton of Dennis Russell Davies. For

this performance, due to logistical issues, only eight Disklaviers were on stage,

but it was nonetheless extremely successful and brought praise from the New

York Times, who said it was "probably the performance Antheil always

wanted to hear."

On June 11, 2000, Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the San Francisco Symphony

Orchestra in a performance of the Ballet mécanique at Davies Hall.

Yamaha again supplied 16 Disklaviers. Tilson Thomas played the piece 15% faster

and and about 25% louder (in terms of the key velocity information being sent

to the Disklaviers) than either of the previous performances, which made for

a tremendously exciting result. The full house responded with a standing ovation

and five curtain calls, and the press was equally enthusiastic.

The piece is now in the concert repertoire, and can be played by any ambitious

group. Although having 16 Disklaviers certainly adds to the drama of the piece,

it can be played on fewer instruments (as long as their number is a multiple

of 4) and they do not have to be Disklaviers: other makes of MIDI-compatible

player pianos such as Mason & Hamlin or Baldwin will also work, and even

good-quality electronic pianos through a powerful sound system would suffice.

The Ballet mécanique was also performed in Antwerp, Belgium,

on August 26, 2000, although as of this writing details are not available. Future

performances are scheduled for Victoria, Canada in 2001, and Essen, Germany

in 2002.

The author wishes to thank Charles Amirkhanian, George Litterst, Tod Machover,

Rex Lawson, and Joseph Crane, and the students and faculty of the University

of Massachusetts Lowell and Tufts University, as well as the companies mentioned

herein. This project was undertaken in partial fulfillment of a Master Of Arts

Degree in Independent Study/Music Performance Technology at Lesley University,

Cambridge, MA. For more information, please contact the

author or visit the Ballet mécanique Web site at antheil.org.

The author will not be present during this

conference. Press or other interested parties can reach him at home in Massachusetts:

781 393-4888.

Copyright © 2000 by Paul D. Lehrman. All

rights reserved Two days later,

most of the concert was recorded in the same auditorium, using a large array

of room and spot microphones, onto 24-track digital tape. When the tape was

mixed, however, it was realized that only four tracks were necessary for 99%

of the mix: a pair of hypercardioid mics in ORTF configuration directly behind

the conductor, and a pair of spaced omnis set a few feet back from the stage

apron. The result is now available on Compact Disc on the Electronic Music Foundation

label (www.cdemusic.org/emfmedia),

and was described by the Boston Globe as a "party record for technophiles,

but just about everyone else will have fun too," and by The Wire magazine

(UK) as "an awesome blast from the past." (If

you have the RealAudio player installed on your browser, click here

for a sample.)

Two days later,

most of the concert was recorded in the same auditorium, using a large array

of room and spot microphones, onto 24-track digital tape. When the tape was

mixed, however, it was realized that only four tracks were necessary for 99%

of the mix: a pair of hypercardioid mics in ORTF configuration directly behind

the conductor, and a pair of spaced omnis set a few feet back from the stage

apron. The result is now available on Compact Disc on the Electronic Music Foundation

label (www.cdemusic.org/emfmedia),

and was described by the Boston Globe as a "party record for technophiles,

but just about everyone else will have fun too," and by The Wire magazine

(UK) as "an awesome blast from the past." (If

you have the RealAudio player installed on your browser, click here

for a sample.)