First Pan-American/Iberian Meeting on Acoustics, Cancun

[ Lay Language Paper Index | Press Room ]

Music in the Urban Soundscape?

Dick Botteldooren- dick.botteldooren@intec.rug.ac.be

Bert De Coensel

Tom De Muer

Department of Information Technology, Ghent University

St. Pietersnieuwstraat 41

Gent, B-9000, Belgium

Popular version of paper 5pNSa7

Presented Friday afternoon, December 06, 2002

First Pan-American/Iberian Meeting on Acoustics, Cancun, Mexico

In the mid seventies, Voss and Clarke [1] investigated the long-term variation in pitch and loudness in various kinds of music that mankind has produced. Much to the astonishment of the acoustic community, they found the same 1/f-noise behavior in almost all of this music. (This sort of spectrum indicates that there is roughly twice as much acoustic energy at a given low frequency than there is at a frequency twice as high.) So, why was this particular time variation so appealing to our ears? What was music trying to imitate? It wasnt until about a decade ago that researchers investigating complex systems realized that 1/f-noise was related to self-organized criticality (SOC), which is the term given to systems with behavior that fluctuates between predictability and unpredictability. SOC was discovered everywhere: the fluctuation of the water level in the Nile, a pile of sand sliding down as grains were added, the fluctuation of the stock market, road traffic flow, etc. Is it possible that we like this critical balance between predictability and unpredictability so much that we reproduce it in our music?

Today, environmental noise is invading the urban society and threatening the quality of life. Yet many people are attracted by the busy hum of a commercial district, or enjoy the murmuring of human voices in the tranquil park around the corner, or even get a kick of the hurly burly of the morning rush hour. This made us wonder if there was some music to be found in the urban soundscape. The easiest, but least sophisticated indicator would be 1/f-noise in loudness and pitch variations. Although quite intriguing from an lart pour lart point of view, this research also has a practical goal. By understanding what people like or dislike in the urban soundscape it may become possible to design this part of our living environment to be more agreeable.

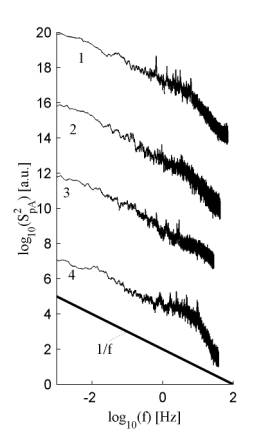

Using modern signal processing techniques, the analyses of a few classical music extracts were repeated. The results are shown below and can be used as a reference for the results presented later.

Spectrum of loudness (pA) and pitch (Z) fluctuation of: 1. The first Brandenburgs Concerto by J.S. Bach; 2. The second piano concerto by S. Rachmaninov; 3. Requiem by W.A. Mozart; 4. The 4 seasons by A. Vivaldi

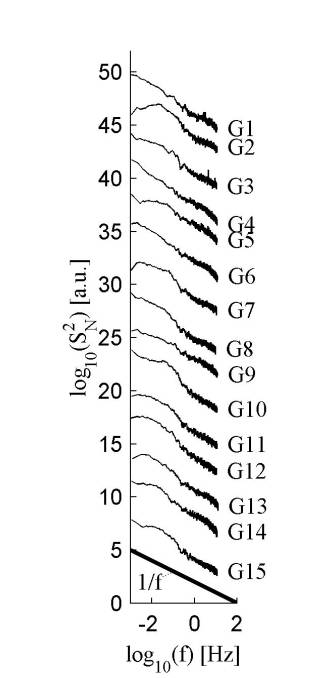

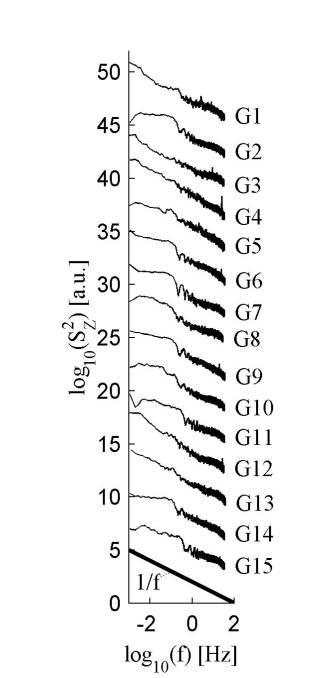

Urban soundscapes were recorded at several locations in the historical city of Gent, Belgium. Each sample has a duration of approximately 15 minutes, and 3-minute excerpts are available for listening on our web server. In contrast to music, the urban sounscape is full of noises that are masked to the ear of the human observer. Therefore loudness must be calculated more carefully. The spectra for loudness and pitch fluctuations are shown in the figure below. In several of the urban soundscape spectra, a straight line comparable to the spectra found when analyzing music appears. Some of the samples scoring high on the 1/f-noise criterion were recorded in traffic-free shopping areas, full of talking people (G9 and G14). Others correspond to a mild mixture of city noises and natural sounds observed in smaller (G13) and larger (G3) city parks. At the locations where traffic noise plays an important role (G2, G7, and G10, in order of importance) there is no straight line evident, indicating that these may not be complex systems at the time scales considered. At the edge of town (G1) both the spectrum of loudness and pitch fluctuation is a straight line, but its slope is between 1/f and 1/f2. Music that has this characteristic would be labeled boring by many listeners. Is natural sound boring music then?

Spectrum of loudness (N) and pitch (Z) fluctuation of 15 urban soundscapes

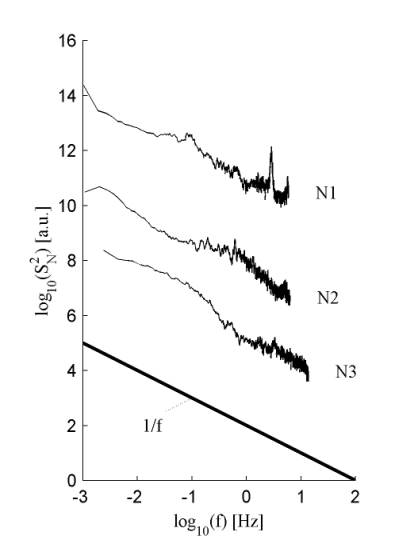

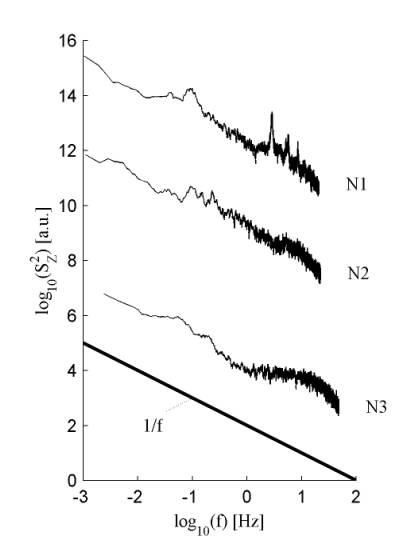

To find out, we embarked upon a quest for interesting natural music. As it turned out one has to travel far and rise early to get away from any plane, train or car noise. In the figure below the sound of the dawn chorus of birds (N1 in a garden soundscape, N2 at the Cornish countryside) and the sound of waves hitting a rock coast (N3) are shown. Clearly, the dawn chorus of birds has a 1/f dynamic both in loudness and pitch. This is something that our music and the chorus of birds have in common. The sound of waves hitting the coast is reasonably close to 1/f-noise except for the pitch variation that seems to be constant at time scales between one and 0.1 second. Is our music just imitating interesting natural soundscapes?

Spectrum of loudness (N) and pitch (Z) fluctuation of 3 interesting natural soundscapes

A few points of ongoing research have not been addressed so far. How can these observations be used in the evaluation of urban soundscapes? Many loudness and pitch spectra show a breaking point between minus one and zero corresponding to periods of one to ten seconds. On time scales below a few seconds the variation of the sound is due to variations in the emission of individual sources. On time scales longer than a few seconds the passage of sources (cars, passers-by) determines the dynamic. The perception of soundscape dynamics may be influenced differently on these two time scales. We are currently starting research aimed at relating the slope in the frequency spectrum on both time scales to subjective perception using test populations. Average loudness is obviously a very important factor for the perception of the acoustic environment. Long-term dynamics of the soundscape, as we defined it in this paper, may be an important additional factor for linking subjective evaluation to physically measurable quantities.

Can the presence of 1/f-noise in the urban and natural soundscapes be a coincidence or has it a physical background? Log-log linear spectral behavior is very common for complex systems. Such systems cannot be characterized by a few time constants. Numerical simulation of multiple particle or multiple agent systems have shown that, broadly speaking, a combination of two simple conditions can result in complex behavior and SOC: a common attractor or group behavior and a nonlinear repelling force. Let us consider bird singing first. Many researchers have studied why birds sing and especially why they form a dawn chorus. Several reasons can be mentioned for birds to start their summer morning by singing. Within one species there clearly is a common optimal moment to start singing. Moreover, the song of one bird may trigger its neighbor to sing. Obviously it does not make much sense to sing whilst nobody is listening. Both elements for SOC are present, an attractive time to sing and a group behavior on one hand and an advantage not to interfere with one another on the other.

SOC in the urban soundscape is much more difficult to explain. The conversation of a group of people may be governed by the same laws of group behavior and non-interference as bird song and therefore could lead to SOC. On a somewhat longer time scale SOC could arise because people tend to flock when walking through a street. Their group behavior urges them to walk together, and yet being too close is clearly uncomfortable, so again both elements are present. If people are talking, they will contribute to the overall 1/f-dynamics in the soundscape. Car traffic was proven to show SOC under certain conditions. Due to traffic lights and other interference with the natural flow, the right conditions may not be present. We are currently investigating urban traffic dynamics and its contribution to the soundscape using micro traffic models.

This paper demonstrates that there is 1/f noise in the loudness and pitch fluctuation in interesting natural sounds just as there is in music. More than expected, these specific dynamics are also found in loudness and pitch fluctuations in urban soundscapes. We put forward the hypotheses that this results from self-organized criticality in the complex urban community. The presence of 1/f-noise could be used as a quality criterion for the urban soundscape, but further research relating it subjective assessment is required.

[1] R. Voss and J. Clarke, "1/f noise in music and speech," Nature 258, 317-318, 1975