Jerald R. Hyde

POB 55

St. Helena, CA 94574-0055

Popular version of paper 1pAAa1

Presented Monday afternoon, May 24, 2004

147th ASA Meeting, New York, NY

1 Introduction

Asking the question "do people go to concerts just for the sound?" is like asking "do people go to a fine restaurant just to eat food?" It has become clear over the past two decades of scientific concert hall research that the answer is "no," in that what we experience at a concert, or in general, is a function of an integration of all our senses.

We will see that at least two acoustical factors are directly affected by visual input, and that visual information is found to be a strong and important issue in how we react to a space and how we perceive the overall experience, of which "the acoustics" is a factor.

A Word on Multisensory Integration

All experience is the result of multisensory integration. It is therefore essential

that, in considering concert hall quality, we also consider "non-acoustical"

issues, since we have evolved as a species by integrating converging sensory

input. The product of the integrating process is "perception." There

are significant differences between "seeing" and "hearing"

as opposed to the perception of an event which uses both senses. Generally,

the visual modality predominates. Where the intensities of stimuli are similar,

the visual effect on auditory perception is greater than the effect of sound

on visual perception. The ventriloquism effect is a well known example.

The Performance as Integrated Experience

The perception of an event, say a recital, concert or an opera, is the result

of the integration of not only the senses but of information previously stored

in the brain relative to preferences, biases and in general our past experience

in the same milieu. It would be hard to imagine that one would easily extract

the acoustical information from the greater experience.

As one views Fig. 1, the rhetorical question one might ask is, "Are these people here for the acoustics?" We are viewing an opening night at the Milan Teatro Alla Scalla, with the women in gowns and the men in tuxedos. The stage will soon be filled with larger-than-life sets, glittering costumes and perhaps even live animals.

We see that these people are taking part in a cultural event, which surely has social, dynamic and visual aspects which are every much as important as the acoustics. Obviously, going to a concert or opera is much more than a unisensory, singular acoustical event. We find that our senses have strong and meaningful interactions.

|

2 Two Acoustical Factors are Found to be Influenced by Visual Input

Intimacy

Acoustical intimacy (herein referred to as Intimacy) is defined as "the

feeling of closeness to the performer," and "as though the music is

being played in a small room." Intimacy was first widely used in the listening

context in Leo Beranek's (a) seminal work on acoustical design in 1962. While

there are objective factors relating to early reflection patterns which have

some correlation with Intimacy, its very definition describes a feeling which

relates to the physical relationship of the listener to the space and the performer.

With feelings of "closeness" and "small room" translating

to dimensional issues, indeed these are confirmed through the visual modality.

The perception of these becomes a combination of acoustical input, supported

and confirmed through visual inspection.

In fact, acoustical research shows us that both the size of a room and the distance between performer and listener cannot easily be discerned solely from the acoustical information (say, with eyes closed). Thus, the only way an observer can determine actual room size and distance from the source with certainty is through visual inspection.

Visual input also plays a less direct but equally important role in the multimodal event in that it allows us to compare our current experience with past events having different aural and visual conditions. This leads to the possibility that expectations based upon past experience may affect our feeling of the current event. For instance, if we see we are quite far from the stage, yet the sound is of a greater strength than we would expect, we tend to judge it as being more Intimate than if we are visually and physically closer to the source, but at the same sound level. This effect has, in fact, been measured and studied in large halls by Hyde and Toyota.

Perception of Loudness versus Distance

Work by Michael Barron in his extensive survey of British concert halls has

also found visual influences on what we hear. Barron reported the combining

of both objective acoustic measurements with the subjective evaluation of the

same spaces during live concert conditions. Of importance is that these results

were derived from the real world experience, including the integrated visual

input, by surveying experienced listeners who attended concerts in the halls

in which objective sound field data were also known.

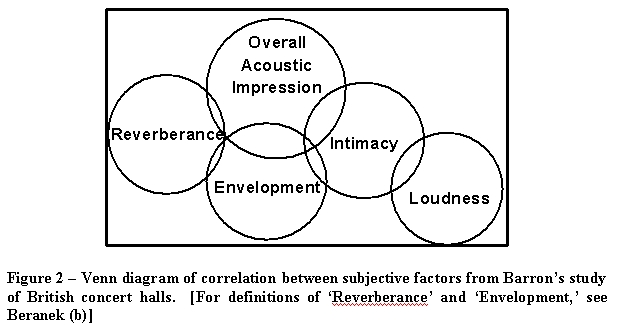

Summarized in Fig. 2, "Intimacy" was found by Barron to be one of three independent factors correlated with "overall acoustic impression" of a space, and importantly he also found a correlation between Intimacy and subjective loudness.

|

Most interesting from these studies is the finding of relationships between Intimacy, sound level and the perception of distance and size of the space. Barron found that the impression of loudness remains constant moving away from the source, even as the actual sound level decreases. Thus, it appears that visual input causes the listener to compensate for the actual drop in the sound level.

These results relate to the phenomenon known in sensory psychology as "perceptual constancy" where the brain extracts a stable world from an ever-changing sensory input. In other words, it allows objects and events to appear stable in the face of their continually changing stimulus features.

3 A Summary of Visual and Other Stimuli Likely to Affect the

Concert Experience

Visual stimuli include the movement of the performer and conductor, the synchronicity of movement and cadence of string and other players and the movement and physical expression of the soloist. The degree to which an observer integrates and uses this information clearly depends on the amplitude of movement and the size of the dynamic image which is inversely related to distance.

Other visual input includes color and the lighting of the performance area and the architectural lighting of the space in general. As to lighting, a noted theater designer has attributed to a famous actress the statement, "There isn't an acoustical problem a good follow-spot can't fix." In general it is found that as audience lighting levels decrease and the lighting focused upon the performer increases, the apparent loudness of the source increases.

As for color, it has been reported that conductors seem to prefer white and gold interiors to blue interiors, and it is well known that musicians believe that wood is essential for successful concert halls. There is anecdotal evidence that indeed the color of a performing space, while not affecting the sound field, appears to have a psychological influence on the listener. In the case of rooms with light and/or blue colors, the music experience has been judged as being "cool." In the case of rooms in darker, wood-toned and/or red colors, the music experience has been judged as being "warm."

Finally, we all know that the overall architectural impression, as well as our physical comfort and the ease of moving about can affect our evaluation of the experience.

4 The Bottom Line for the Concert Experience

For a great concert experience, be sure to leave your problems at home, enjoy a satisfying dinner, find a good parking space, arrive early, don't fight the freeways, and get your favorite seats. Watch your favorite performance in a nicely lit and tastefully designed space at just the right temperature and humidity. The hall, of course, will have good natural acoustics, with great clarity, good sound strength, reverberance and warmth of tone, all contributing to a wonderful evening. And, you probably won't think much about the acoustics, if at all.

References

Leo Beranek, (a) Music, Acoustics and Architecture, Wyle, 1962;

(b) Concert Halls and Opera Houses - 2nd Edition, 2004.

Jerald Hyde, 17th ICA, Rome, Paper 5A.11.02, September 2001

Yasuhisu Toyota, et al., JASA, Vol. 84 (S1), 1988.

Michael Barron, (a) Acustica, Vol. 66, 1988; (b) 12th ICA, Toronto, Paper E4-3,

1986.

Acknowledgment

The peer and lay review of Joel Lewitz and Robin Peters is gratefully acknowledged.