151st ASA Meeting, Providence, RI

Quiet, I'm Trying to Learn language!

The Effect of Background Noise on Infants

Rochelle Newman- rnewman@hesp.umd.edu

Dept. of Hearing & Speech Sciences

University of Maryland

College Park, MD 20742

Popular version of paper 3aSC22

Presented Wednesday morning, June 7, 2006

151st ASA Meeting, Providence, RI

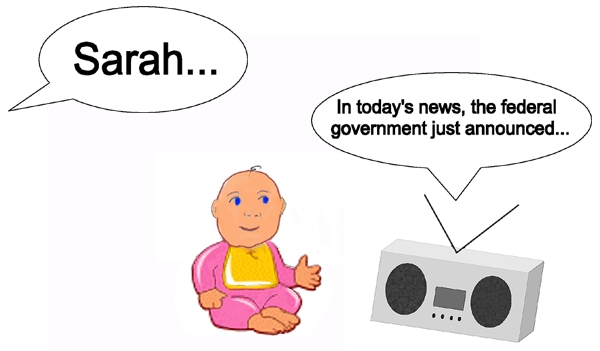

Cars screech across the TV screen; siblings bicker in another room;

the blender whirrs in the kitchen; and somehow, in the midst of all

the noise, an infant sifts the sound of her own name out of the

tumult and responds.

This environment, typical of modern households, could not be more

different than the quiet laboratory settings in which most research

on how infants learn language has taken place. The present research

examines how the type of background noise influences infants' ability

to understand speech.

The study examined how long a 4.5-month-old child spent listening

when a female voice said either the baby's name or another infant's

name in the presence of background noise. Prior research in quiet

labs has shown that at 4.5 months, babies will listen longer to their

own name than to someone elese's (Mandel, Jusczyk & Pisoni, 1995). We

examined if this would hold true in the midst of different types of

noise.

In particular, we compared a situation akin to a day care (with

multiple people talking in the background) to something more common

in a home setting (with only a single person talking in the

background).

Testing

Infants sat on their caregiver's lap in a three-sided booth. A light

on one of the side panels attracted the infants' attention; once the

infant was looking in that direction, the woman's voice began calling

a name. On some trials, the name was that of the infant being

tested; on other trials, it was the name of a different child. The

woman continued to repeat the name until the baby turned his or her

head away, and we measured the amount of time each infant spent

listening to the different names. In all three cases, the target

woman's voice was 10 decibels louder than the sounds of the other

people talking; this is roughly equivalent to the noise level you

might experience while having a one-on-one conversation at a

reasonably quiet restaurant (one filled with other patrons, but in

which people are speaking softly).

Results

Infants heard the names in the presence of three different types of

noise: a mix of multiple background talkers, a single background

talker, and a single background talker reversed in time (this has the

acoustic properties of a single talker, but doesn't sound like real

speech) ; examples of these sounds are presented below.

When the noise consisted of multiple people speaking at the same

time, infants listened longer to their names than to the names of

other children. However, they only did so when the target speech was

at least 10 dB more intense than the background - a less noisy

situation than that typically found in day care settings (see, for

example, http://www.acoustics.org/pressroom/httpdocs/139th/golden.htm).

Sample 1

Sample 2

But even at this high amplitude level, infants appeared able to

recognize their own name when the background noise blended to a

murmur, but clearly found the task far more difficult when the

background signal was a single voice. This is particularly

surprising, because adult listeners show the exact opposite pattern.

Sample 3

Sample 4

Summary:

The present results suggest that listening in noise is a more

difficult task for infants when the "noise" consists of a single

talker than multiple talkers. Moreover, this was the case even when

the talker was much louder than the background noise.

These findings suggest that children may experience difficulties

listening in many of the settings where they commonly find

themselves. Often, in the home, background noise takes the form of

other voices, and there generally may not be so many other voices

that they blend into background babble. A parent may be talking to

her infant while someone is talking on the phone, or while the other

parent is speaking to a sibling. These situations are much more akin

to the single-voice condition presented here, and the present results

suggest that infants may have a very difficult time understanding

what is said to them in these situations. Moreover, the fact that

adults show just the opposite pattern suggests the possibility that

parents may frequently underestimate the extent of the noise problem

facing their child.

These results imply that noise could interfere with children's

language development, suggesting the need for greater parental

awareness of the noise in their infants' environments.

[ Lay Language Paper Index | Press Room ]

|