151st ASA Meeting, Providence, RI

Suppression of Offensive Chants at Sporting Events

Through Feedback of Sound

Sander J. van Wijngaarden -- sander.vanwijngaarden@tno.nl

Johan A. van Balken

TNO Human Factors

P.O. Box 23, 3769 ZG Soesterberg

The Netherlands

Popular version of paper 3aPP9

Presented Wednesday Morning, June 7, 2006

151st ASA Meeting, Providence, R.I.

Few things can disrupt the mood of a sporting event more than an offensive or otherwise

inappropriate chant. Some sports federations, which have a keen interest in keeping the

game fun for all audiences, even have elaborate systems of fines and penalties: if supporters

persist in chanting inappropriately, then the team they are rooting for is punished.

It is, in fact, not easy to initiate a chant. A chant can only be launched successfully

if enough people are willing and able to join in. It is normally very hard to influence

how many people are willing to join in with offensive chants. However, measures can be

taken to reduce the number of people who are able to do so. An often-tried technique is

masking of chants by means of loud music. This approach has a clear drawback: the sound

level needs to be very high in order mask chants effectively. Very loud music during the

game is usually not appreciated by sports fans, let alone by the players.

Rather than just creating a louder kind of noise to mask a chant, a more elegant approach

would be to confuse the chanters. There is a known mechanism to confuse a talker or singer

on purpose, called "delayed auditory feedback. While a person is talking, the sound of his

voice is fed back to him, after introducing a small delay of only a fraction of a second.

The delayed sound is usually played back through headphones. The effect is that the person

in question starts to speak more slowly, starts to stutter or starts to repeat and omit

words. The question is: can this principle also be used to confuse a larger group of people,

who are trying to chant synchronously? The effect of delayed auditory feedback on individuals

has been studied extensively. Its effects on groups is less clear: people will not only react

to the sound of their own (delayed) voice, but also to the sounds from other chanters.

Also, sound will need to be fed back by means of loudspeakers rather than headphones.

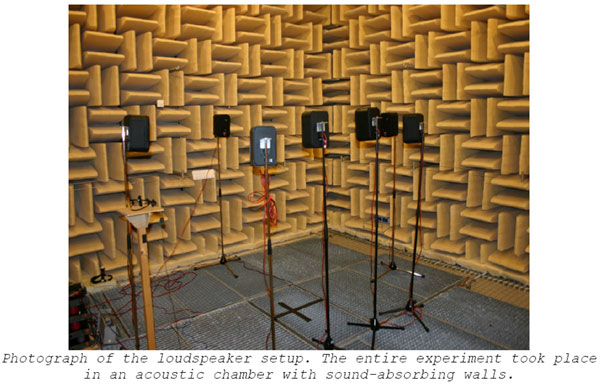

In order to find out whether delayed feedback sounds can in fact be confusing to a chanting

sports fan, a laboratory experiment was carried out with 16 participants. These participants

took part in the experiment one at a time; a surrounding group of chanters was simulated by

means of loudspeakers.

By letting the participant take part in a "simulated" chant based on audio recordings, the

experiment could be carefully controlled. The participant's own voice was recorded during

the experiment. These recordings were used to determine whether the participant was able to

keep his timing synchronized to the other (simulated) chanters, or if his timing was affected

by the delayed feedback sound. Also, participants indicated whether they felt as if their

attempts to join in with the chants were being frustrated.

This laboratory experiment showed that all participants could be frustrated in their attempts

to join in with the simulated chant. By analyzing their voice recordings, the participants

could be shown to lose track of the chant, and apply their own version of the timing and

rhythm of the chant. They also indicated that they felt frustrated in their attempts.

The degree of disruption was found to depend mainly on two factors: the loudness of the

delayed feedback sound, and the delay time. To achieve a sufficient degree of disruption,

the delay time must be at least 0.2 seconds. Longer delay times (up to 1 second) tend to

be more effective than shorter delay times. The louder the feedback sound, the more disruptive

it is. In general, the feedback sound must be at least (nearly) as loud as the original chant

in order to be effective. Unfortunately, feedback sound tends to be less effective if the

signal quality is low. This was tested to verify the effects of relatively poor quality

sound systems (commonly found in sports stadiums). Also, if the feedback sound is clearly

coming from one direction, while the original chanters are all around, the effect is

clearly reduced.

Since the experiment took place in a controlled laboratory setting, its outcome does not

tell us whether the principle can actually be applied to suppress chants by real fans,

in real sports arenas. At least two complications arise when taking the concept from the

laboratory into the stadium:

- Real fans act jointly as a group, which can be highly motivating. Perhaps

groups of real fans are not as easily disrupted in their "natural environment"

- Large-scale use of loud feedback signals are likely to create technical problems,

especially in environments with echoes or reverberation

To gain a better insight into these two issues, two field trials were organized,

one with 350 and one with 115 participants. These trials were not intended to be highly

structured scientific experiments, but rather as a first exploration of the possibilities

of delayed feedback in a more realistic setting. The field trials have shown that groups

of chanters subjectively do experience disruption, but are generally able to

continue chanting as a group. The reason is the limited loudness of the feedback signal:

the straightforward sound systems used in these field trials tended to show uncontrollable

feedback behavior (such as whistling noises) at the required sound levels.

Devices known as "feedback destroyers," which are relatively standard in professional audio

reproduction, may help to solve this problem. This has not yet been tested.

At this point, chant suppression works in theory, but not (yet) in practice. Nobody should

expect to experience the effects of chant suppression during his next visit to a stadium.

However, with more sophisticated audio components and further testing, we believe our

approach will become increasingly feasible for real-world applications.

[ Lay Language Paper Index | Press Room ]

|