Camille Desjonquères1,2,3 – desjonqu@uwm.edu

Fanny Rybak3, Toby Gifford4, Simon Linke5, Jérôme Sueur2

1 Molecular and Behavioural Ecology Group, Department of Biological sciences, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, United States

2 Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Institut Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité, ISYEB, UMR 7205 CNRS MNHN UPMC EPHE, 45 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France

3NeuroPsi, CNRS UMR 9197, Bâtiment 446, Université Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay cedex, France

4SensiLab, Monash University, Caulfield, VIC 3045, Australia

5Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD, 4111, Australia

Popular version of paper 1pAB1

Presented Monday afternoon (1:00-1:20 pm), November 5, 2018

176th ASA Meeting, Victoria, Canada

Healthy freshwater environments are essential to the survival of many living organisms including humans. Disturbingly, these environments are so impacted by human activity that biodiversity is declining faster in rivers and lakes than any other type of environment: between 1970 and 2012 populations declined by 81% in freshwater systems compared with 38% and 36% for terrestrial and marine systems respectively (WWF, 2016). Action must be taken to protect these environments, and for this efficient monitoring of ecosystem condition is crucial.

There are several sources of sounds that can be heard underwater in lakes and rivers. Many animals communicate through sound, including frogs, fish (Fig. 1), insects (Fig. 2) and some crustaceans. Water flow and pebbles rolling at the bottom of rivers and streams can be very informative about the physical structure of the environment. The most surprising source of sound may be that of breathing and photosynthesizing plants (Fig. 3).

Figure 1: Video of a pool with spangled grunters (Leiopotherapon unicolor) and juvenile sooty grunters (Hephaestus fuliginosus). Both species are emitting grunts. Recorded in Talaroo (Queensland, Australia).

Effective restoration and protection actions requires detailed knowledge of the environments. It is therefore necessary to survey and monitor freshwater environments. Most current methods used to survey freshwater environments such as netting and electrofishing suffer some limitations: (i) they can injure wildlife, (ii) they only provide a snapshots of the environment, and (iii) they can require a significant workforce. In this presentation, we propose that using sounds recorded underwater with hydrophones is a powerful method to survey freshwater environments.

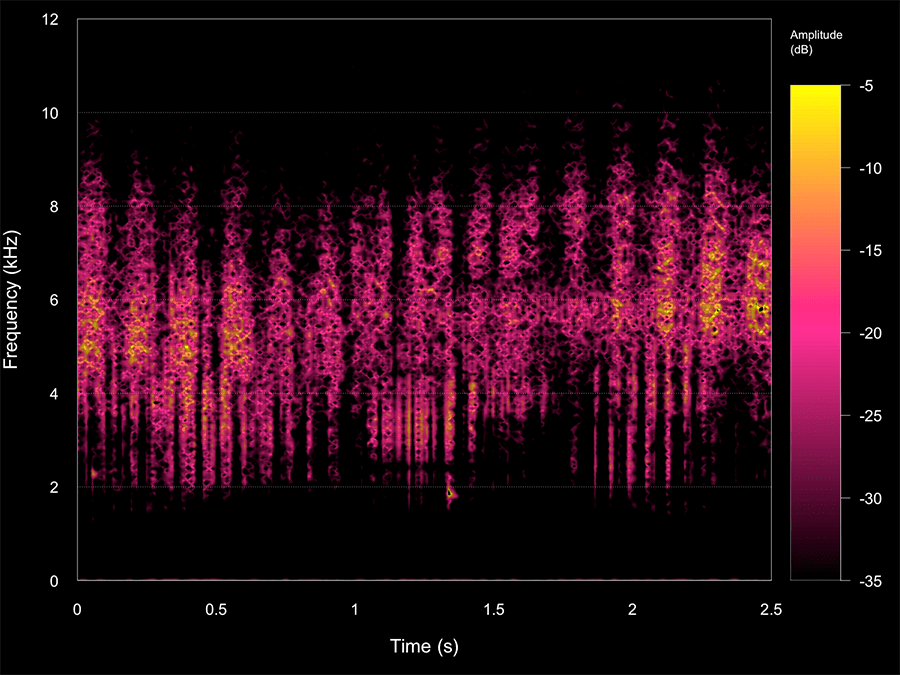

Figure 2: Spectrogram and associated recording of a true bug (Hemiptera) chorus recorded at night in Talaroo (Queensland, Autralia).

The use of sounds recorded in the environment for ecological surveys is studied in the field of ecoacoustics. Ecoacoustic monitoring relies on non-invasive methods that only require the introduction of an acoustic sensor in the environment. Automatic recorders allow for continuous monitoring and reduces the amount of workforce required. Freshwater ecoacoustic monitoring therefore seems like a great complement to more typical surveying methods.

Figure 3: Video of a plant expelling gas bubbles underwater and associated hydrophone recording (Video courtesy of François Vaillant). The legend in the video at 4 seconds reads ‘little bubbles coming out of the leaf’ and at 30 seconds says ‘a ‘big’ bubble is forming at the surface of the leaf’.

Ecoacoustic monitoring is an extremely promising method, already used in terrestrial and marine environments, but that is yet to be operationalized in freshwater environments. Our current research aims at standardizing temporal and spatial sampling designs as well as investigating the links between acoustic and habitat condition in freshwater environments. Overcoming those challenges will allow the application of ecoacoustic monitoring to a broad range of conservation and ecological research questions including the detection of rare or invasive species as well as condition surveys (e.g. polluted vs pristine) or rapid biodiversity assessments.

References:

WWF (2016) Living Planet Report 2016: Risk and Resilience in a New Era. WWF international, Gland, Switzderland.